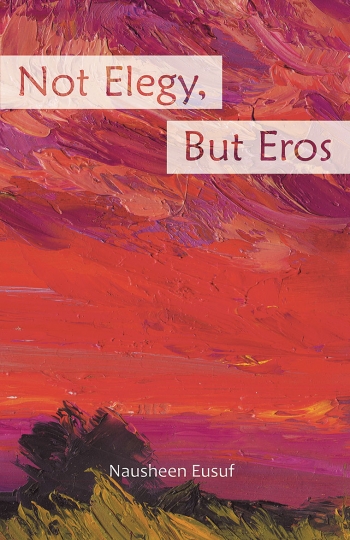

Nausheen Eusuf ’02 grapples with grief in her debut collection of poems, Not Elegy, But Eros. The work has earned rave reviews from the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Best American Poetry blog. Born and raised in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Eusuf majored in computer science at Wellesley, but is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in English at Boston University. She says her career path in the past 15 years, including writing the book, is a direct result of the Wellesley class she took with Frank Bidart, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities and professor of English, during her senior year.

How did Frank Bidart teach you to read poetry?

I had never studied or written poetry before his class, but just hearing him read was like a religious conversion. He embodies poems and brings them alive. Often I would read a poem at home and wouldn’t understand it. Then I’d hear him read it, and his performance of the poem enacted what the poem was doing on the page—through rhythm, cadence, intonation, etc.—and suddenly it would start to make sense.

There are many losses in the book, both personal and public. How did writing help you deal with loss?

I started writing poetry around the time my mother’s health was deteriorating (she had kidney failure), and she died while I was doing my M.A. in creative writing at Johns Hopkins. My father never recovered from the loss—he died less than two years later. Writing about grief was a way of coping. Later, I began writing public elegies for victims of political violence or terrorist attacks—writing about it is a way of dealing with the despair and horror of witnessing such events.

But the book is also about transcending grief and affirming life, isn’t it?

Although I started out writing mostly elegies following my parents’ deaths, eventually I found other things to live for, other ways of finding meaning and purpose. Finally, in my late 20s, I turned toward life, rather than away from it. And that change is reflected in the formal and emotional range of my poems. The book is titled Not Elegy, But Eros because there’s a conscious choice to move away from the elegiac, and to affirm life and the living: Eros, as the life force, as an antidote to Thanatos. That’s the overall arc of the book.

Lund reviews poetry each month for the Washington Post.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.