Illustration by Stuart Bradford

When violent protests seized Haiti in early 2019, Michele Sison ’81 flew into overdrive. Transportation in the country was paralyzed, businesses closed, and public and private property was destroyed. The United States government issued a travel warning, Haitian children missed school for weeks, and residents went without food, water, and gas.

Through the chaos, Sison, the U.S. ambassador to Haiti, saw her role clearly. She and the U.S. embassy were in a unique position to act as a convener—to cool the tension on the streets by creating a space for all parties to come together.

“The Haitian people were really paying a price,” Sison said in an interview shortly after the wave of violence subsided. “The violence, of course, leads and led to further instability and suffering for Haitian families, the average Haitian people.” She spoke with the cool demeanor that could only come to someone who has devoted four decades of her life to foreign service in some of the most volatile political climates our world has ever seen.

The embassy quickly put those convening powers to work. Sison and her staff brought together top Haitian government and opposition leaders, businesspeople, and regular citizens—all to try to tamp down the situation. It was crucial, Sison says, to foster “a constructive and inclusive national dialogue.” All parties involved needed a space to “express themselves peacefully,” she says.

Asked if she fears the risk that comes with living and leading through such a dangerous situation, Sison says she is more focused on serving Haiti as a representative of the U.S., a close ally. “We happen to be here just a couple of hours away from the United States, so we’re a close neighbor, and we’re a longtime friend of Haiti,” she says. What keeps her going, she says, is a genuine commitment to securing prosperity, democracy, and stability in Haiti.

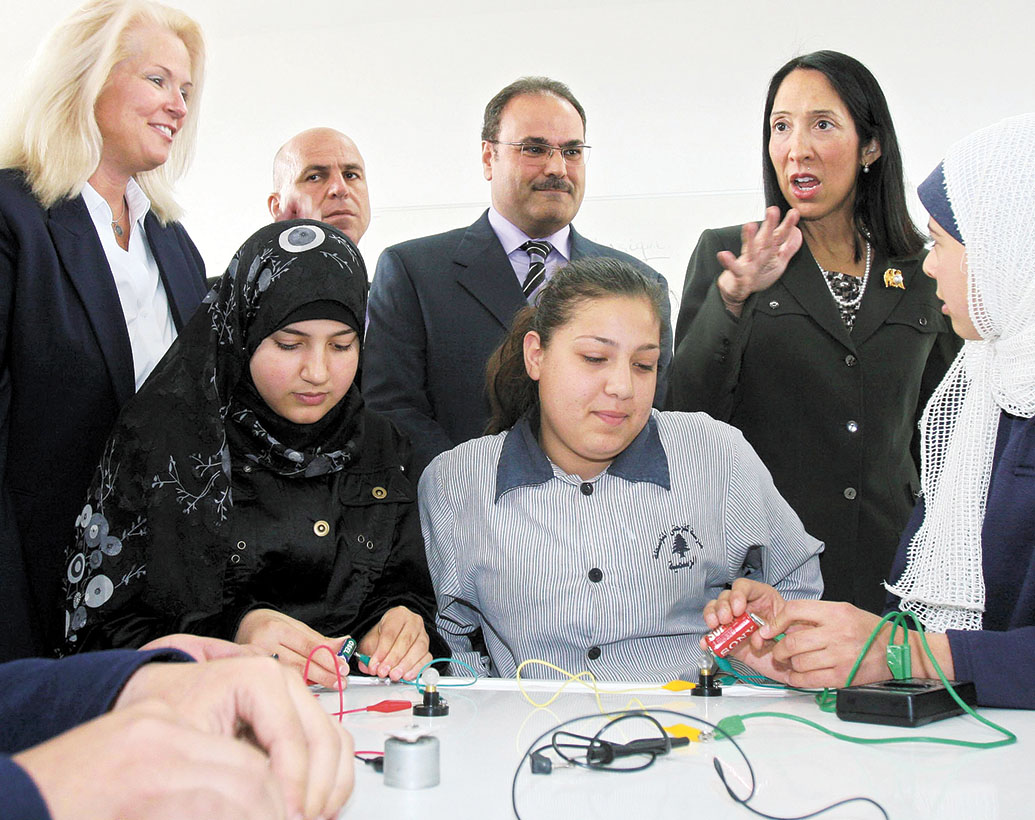

Michele Sison ’81

Photo by Bloomberg/Getty Images

Over the course of her career, Sison has endured dangerous assignments across the globe, frequent moves, and an unpredictable lifestyle. But she and the other alumnae who have dedicated themselves to the State Department and foreign service say, despite the challenges, the professional and personal rewards are immeasurable. They follow the path out of a deep sense of service to the U.S. and the world—and become full participants in America’s relationship with the world. These alumnae embody Wellesley’s motto—not to be ministered unto, but to minister—to their cores.

“I think for all of us in the Foreign Service,” Sison says, “it’s that second word, service, that we really feel drawn to.”

More than 8,000 miles away in Tokyo, Jessica Berlow ’03 acts as a convener of a different sort. She oversees the U.S.-Japan alliance as a political-military officer in the State Department. The alliance is a long-running security partnership, developed after World War II, that plays a central role in East Asian geopolitics. Berlow manages and analyzes U.S. military basing in Japan, Japan’s own defense policy, and Japan’s defense relationship with Korea, Australia, India, and others in the region.

“So right now, the hot topic for me,” she says, “is looking at how Japan plans to implement two brand-new, long-range defense policy plans … and where do the United States and other allies fit into that?”

On a typical day, she meets with counterparts at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defense to talk about big questions: “What is Japan looking to do to respond to situation X in the region, or how does Japan envision working with the United States on problem Y?” She and her office also support senior-level visits from the U.S., including the secretaries of state and defense and congressional delegations.

Berlow’s interest in the region was inspired by the Japanese department at Wellesley, which encouraged her to study abroad for a year in Kyoto. “One of the best experiences of my life,” Berlow says. After graduation, she returned to Japan on a Fulbright Fellowship to study the U.S.-Japan defense relationship.

She now speaks Japanese, Mandarin, and Spanish, and says Wellesley gave her the support to really challenge herself while “hearing the message from folks around me that I could do this, no matter what the obstacle was.”

Her return to Japan as a State Department officer was different. “Having studied Japan from an academic angle for many years, both at Wellesley and at grad school,” she says, she really wanted to “have a chance to be a full-time practitioner of the alliance and how we manage that alliance with Japan.”

Ambassador Sison’s list of postings over her 37-year career reads like a tour of U.S. foreign-policy hot spots: Haiti, Togo, Benin, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, India, Pakistan, Iraq, United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, Sri Lanka and the Maldives, the United States Mission to the United Nations, and, now again, Haiti.

She was recently named a career ambassador, the State Department’s highest diplomatic rank. She is also a recipient of the U.S. Presidential Distinguished Service Award and several State Department awards, including for her work on counterproliferation and human trafficking.

When Sison was named ambassador to Haiti in February 2018, it was a homecoming of sorts. Haiti was at the beginning of that list—her first Foreign Service assignment in 1982, soon after she graduated from Wellesley. She described it as a full-circle experience, and says she was “very excited and very happy” to return.

Jessica Berlow ’03

Photo by Casey Brooke

When she’s not responding to local emergencies, she leads programs that strengthen Haiti’s democracy and the lives of its citizens. That includes everything from access to health care and education to helping women run for office or create small businesses. Her embassy recently supported the Haiti Tech Summit—deemed the “Davos of the Caribbean.”

As a Filipina-American growing up in Virginia, Sison says she developed an interest in communicating across cultures early on.

When she has lived abroad, she often has been asked: “Where are you from?” followed up with “You don’t look like an American”—a question and assumption that makes many people of color in the U.S. cringe. But Sison says it’s her favorite question because it opens the door for her to share the story of the U.S. and all its diversity. She’ll talk about her own family’s history and America’s “unique ability to use our diverse backgrounds to produce the place in the world that we have today.”

Attending Wellesley broadened her understanding of the world and how interdependent its issues are. She still recalls a specific class discussion with Professor Rob Paarlberg on international food and agriculture policy in which she learned that food insecurity is about so much more than one person not having enough food to eat. It is political, economic, and social—and a women’s issue. “Women, at the end of the day, are trying to make sure that their families are fed and their children have the proper nutrition.”

Like Berlow, Sison is now an active practitioner in the issues she once learned about in a classroom. In Haiti, she says food insecurity is “on my front burner … as we look at the effects of a drought in some of the areas of Haiti combined with some of the challenges in the urban areas that we’re seeing … I’m dealing with those issues on food insecurity and working with USAID today.”

Less than one year after Berlow was accepted into the Foreign Service, she found herself heading to the U.S. consulate in Lahore, Pakistan, in March 2010.

After a graduate degree in international relations from Johns Hopkins University, she entered a prestigious government training program as a Presidential Management Fellow. She was assigned to the State Department in the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, working on counternarcotics in Pakistan and Afghanistan. While at State, she decided to take the oral exam for the Foreign Service.

Becoming a Foreign Service officer is hyper-competitive—out of tens of thousands who may apply each year, only hundreds are selected. “We look for motivated individuals with sound judgment and leadership abilities who can retain their composure in times of great stress,” the State Department description of Foreign Service officers reads, “or even dire situations, like a military coup or a major environmental disaster.”

Partly because she was already working at the State Department, it was an unusually fast process for Berlow. She completed Foreign Service training and did a stint at the State Department’s Pakistan desk in Washington to prepare; then, she was “thrilled” to be assigned to Lahore.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.