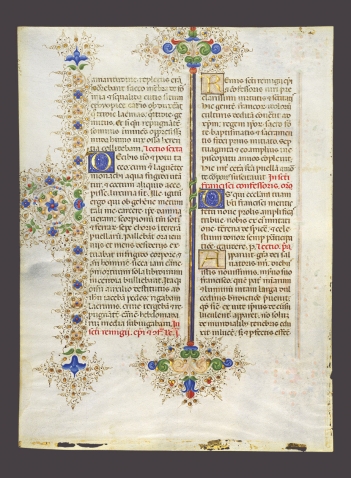

Working in Boston in the early 1960s, Nancy Hattox Fohl ’59 rarely passed by Goodspeed’s Book Shop without going inside. She and her husband, Tim, were attracted to an exquisite illuminated manuscript leaf, which they bought from the bookseller for $13, unframed.

The Fohls’ leaf was once part of a devotional book created for a renowned patron of 15th-century Renaissance Italy. How its leaves came to be sold in Boston is the story of a duke, a baron, and a bookseller. Today, a 21st-century digital project aims to bring the book’s pages together.

In 1441, the Marchese of Ferrara, Leonello D’Este, commissioned the book, known as a breviary, for his family’s chapel. Breviaries served as daily guides to the liturgical year, with calendars as well as psalms, readings, and prayers. D’Este spared no expense: A team of the finest scribes and painters worked for seven years to create the 500-page book, which contained small paintings and illuminated texts.

The book survived a move from Ferrara to Modena, and eventually to Spain. British soldiers may have carried it out of Spain as booty in the Napoleonic Wars. It came to be owned by John Allan Rolls, the first Baron Llangattock of Monmouth, Wales, and father of the co-founder of Rolls Royce. His title gave the book its popular nickname: the Llangattock breviary. In 1958, the book was sold at auction, and the buyer was George Goodspeed of Boston.

Goodspeed disassembled the book (illustrated leaves had been cut out before the book came to auction) and sold the individual leaves—a common practice at the time. The trade in illuminated-manuscript leaves as works of art created an incentive for the dealers, who could realize huge returns on their investments by selling leaves separately.

When the Fohls bought their page in 1962, they marveled at the dazzling colors and delicate pen work. Over time, they became concerned that the page was subjected to too much light in their home. They considered donating it to a rare books library, and settled on Wellesley’s Special Collections at Clapp Library.

Ruth Rogers, curator of Special Collections, was thrilled. The timing was uncanny. She had just attended a conference presentation about the Llangattock breviary, given by another Wellesley alumna, Debra Taylor Cashion ’74.

Cashion, a digital humanities librarian at St. Louis University, started a project called Broken Books to compile a digital record of the Llangattock breviary. So far, she’s identified 90 leaves, some of them in university libraries throughout the United States. “It’s like putting together a jigsaw puzzle,” Cashion says. “And the pieces are all over the world.”

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.