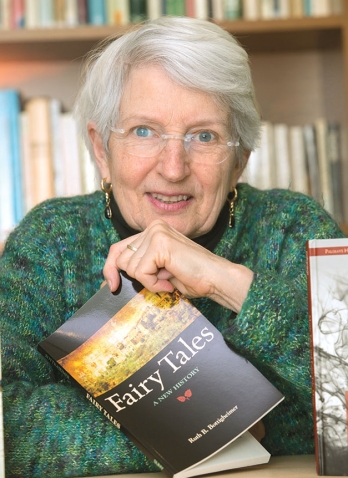

Photo by John Griffin/SBU Communications

In fairy tales, things are rarely what they seem. A poor girl is really a princess. A frog is really a prince. The same can be said of the tales themselves, says Ruth “Sue” Ballenger Bottigheimer ’61. “What you see and what you think about fairy tales has been so covered over by layers of assumptions that it takes real research to figure it out,” she says. Sue is a literary scholar and folklorist based at Stony Brook University, and that sleuthing has been the focus of her 40-year career studying these short narratives.

Take, for instance, the collection of tales known as The Arabian Nights, or One Thousand and One Nights. It is often thought of as a cohesive work that emerged from the Arabic folk tradition of the 8th through 15th centuries, but Sue attributes nearly a third of the tales—including the best-known stories featuring Ali Baba and Aladdin—to the early 18th century, when a French translator needed to expand and recorded stories from a 19-year-old Syrian Christian. Sue has just finished writing a book (her sixth), Inventing Aladdin: The Arabian Nights, Antoine Galland, and a Boy from Aleppo, outlining that authorial sleight of hand.

Her own career has also had its own fairy-tale qualities. A girl from Kentucky shoots for the stars (lands at Wellesley), goes on a journey (a junior year abroad in Munich), then marries a boy (maybe not a “prince,” but a historian, Karl Bottigheimer).

At just the point when the narrative usually goes out of focus in “happily ever after,” Sue wrote a new story for herself. “I have had an atypical career,” she says. While a young faculty wife in Berkeley, Calif., she completed a master’s degree in German just three days before her first child was born. A second child, Hannah Bottigheimer ’88, was born three years later. After following her husband to Stony Brook, she completed a doctorate there in 1981. “Then I got a job at Princeton to everybody’s astonishment, including mine,” she says. “I was 41.”

While at Princeton, and subsequently from her permanent academic home at Stony Brook, she has earned a reputation as one of the country’s foremost scholars of European fairy tales and has developed a novel reading of their origins. Her big idea, which she outlined in a previous book Fairy Tales: A New History, is that many of the eigentliche Märchen—the “real” fairy tales we know from the Brothers Grimm and elsewhere, in which a poor boy or girl suffers through magic and then marries royalty—are not folk tales that rise up out of a rural oral tradition but were the invention of an urban merchant class, circulated by the printing press.

“[Many of these stories] involved a sudden shift from poverty to wealth, and it bubbled up over the years that this is not the sort of thing that comes about in an agrarian economy, where from one generation to the next you might add to your landholdings by a couple of acres,” she says. “Only in cities with a money economy can this sudden wealth take place.”

It is a controversial idea, which garnered heated debate in a volume of the Journal of American Folklore devoted to her thesis, but it has also earned her a Fulbright fellowship, as well as fellowships at the universities of Cambridge, Oxford, Vienna, Gottingen, and Innsbruck. “As an independent scholar, I’ve had all the icing of an academic career without the cake of committee meetings,” she says. This past winter, Sue was recognized with a lifetime achievement award from the Thuringian Fairy Tale and Legend Society in Germany.

At the point when another person might think about slowing down, Sue, who is 81, has turned her sights instead on another book project: this time on the very nature of storytelling itself. “I sometimes ask myself, ‘Why don’t I put my pencil down,’ but one thing leads to another,” says Sue. Like Scheherazade, as soon as she finishes one tale, she begins another.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.