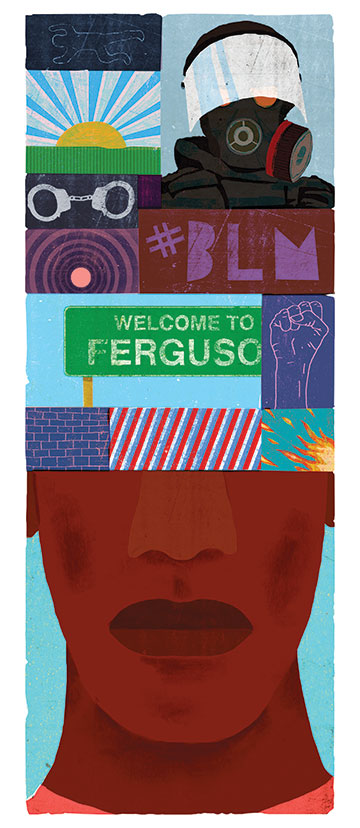

At every turn, the 2016 presidential campaign is setting itself apart from those of years past in huge ways. There are more candidates than space on the debate stages, and there is seemingly endless media coverage, more rhetoric, more money, and more activism. While the country is getting amped up with November in sight, Wellesley is hitting the pause button to take stock of some of this election’s most significant issues and trends. Six of the College’s own are here to help guide you through this unpredictable election. They’ll catch you up on how the Black Lives Matter movement and social media are leaving their mark on the campaign, whether the media’s role has gotten too large, why it’s getting harder to conduct a good poll, and why we’re in, as one professor says, “an amazing period in American political history.”

Metaxas is a professor of computer science who researches the way the web is changing the way we think, decide, and act.

Can social media predict the outcome of elections?

What people and candidates say on social media sites like Facebook and Twitter does not predict the outcome of elections. It’s maybe a little closer than it used to be, but nowhere close to actually having any predictive power. Traditional polls depend on good representation. Social media is a different species: It’s an open forum where anybody can say whatever they want, as they want.

In computer science, we have the so-called incomputability theorem that says there are some things you cannot compute. Even if social media were able to predict elections, there would be so much interest in the influence of these mediums that it would become unpredictable. You know, it’s not a real theorem, but it gives us a sense of why it’s not going to work.

What [social media] is used for, very effectively, is to cheer your troops, to make them feel really excited, and to make them feel that they have a purpose and that you listen to them, as opposed to just measuring how many [followers] you have. If you like to hear from [a candidate] from time to time, when he or she says we have to do something, it can enhance your desire to support the candidate and make you more likely to go out and volunteer. It can also make you more informed, which is important so that you could have, and win, an argument—which is what we humans care most about.

My current research has to do with a tool [we developed] called TwitterTrails: We have found some remarkable ability in actually figuring out, through the power of the crowd, whether something that is spreading is true or false and what the level of skepticism is. It’s based on the idea that when people are not emotionally charged, it’s unlikely that they will try to fool you. They might either choose not to repeat what you said and not propagate it further, or they might question your motives and insert some kind of skepticism. But when it comes to elections and politics, that’s not the case. We see huge polarization for the American elections.

You can also expect a lot of excitement on social media just before the elections. If you spread a lie just two days before elections, chances are it’s going to work. So I am sure there are zealots out there who are designing their strategy. In particular, they try to do what we call micro-targeting—try to find the 40-year-old who lives in a contested area of the country, and try to influence that person.

What are you watching for 2016?

It is early to make any kind of prediction on 2016, but we are collecting data. More generally, I’m curious to see how the large field shakes out. I’m interested in trying to study the moment in which suddenly, a candidate will start rising above the rest. I’d like to know how these changes might be represented in the way they communicate, and I’m interested in knowing what contributes to that moment. I suspect it’s going to be some national news or event, but it could be something else.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.