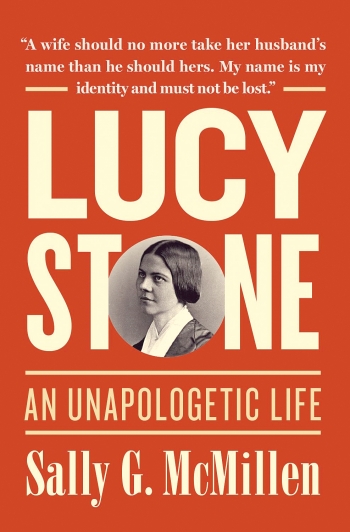

If suffragist Lucy Stone’s name is recalled at all, it’s likely because she kept it when she married, as an act of rebellion against women’s second-class status in 19th-century America. Because women had no rights to divorce, custody of children, wages, or property, Stone resisted marriage until Henry Blackwell promised her an equal partnership.

Stone’s entire life was an example of hard-won independence. Born in 1818, this hardworking Massachusetts farm girl saved her teacher’s salary to pay for a rare college education. She was among the first women to graduate from Oberlin, the only college then admitting blacks and women. She traveled across the north, as an agent for abolition and women’s rights, both radical concepts in the 1850s. After the Fifteenth Amendment enfranchised black men, she led the American Woman Suffrage Association to win another constitutional amendment for woman suffrage and published The Woman’s Journal, the major newspaper covering the women’s rights movement.

Lucy Stone was petite, commanding, formidable—and forgotten. Her former friends, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, became rivals, founders of the National Woman Suffrage Association. They excluded her from The History of Woman Suffrage, a primary source for future historians. Nor, as Sally McMillen notes in her introduction, is Stone included in Adelaide Johnson’s sculpture of suffragists Stanton, Anthony, and Lucretia Mott, now in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda.

Until they uncomfortably merged in 1890, members of these competing suffrage associations debated which was the first women’s rights convention (Seneca Falls, N.Y., in 1848, organized by Stanton, or Worcester, Mass., in 1850, attended by Stone) and whose strategy was most effective (federal versus state action). Their list of mutual grievances foreshadows the schisms that would undermine contemporary feminist campaigns.

Davidson College professor McMillen has crafted a thoroughly researched, graceful, and engaging biography. And Stone is worth recalling, not only for her relentless pursuit of equal rights but also, and equally interesting, for her struggle to balance a public life with marriage, motherhood, menopause, and housekeeping. She earned more money and fame than her husband, who struggled to find a steady career before joining her as a reform speaker and editor. Their only child, Alice Stone Blackwell, was also part of the family enterprise.

Lucy Stone died in 1893, 27 years before the Nineteenth Amendment passed. Her last words were “Make the world better.”

Griffith is the author of In Her Own Right, a biography of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone’s rival.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.