Alexa Rodriguez ’17, Amina Ziad ’17, and Alexandria Otero ’19

Photo by Kathleen Dooher

When Karen Su ’19 finished canvassing and working the phone banks on Nov. 8, 2016, she felt confident voters would elect Hillary Rodham Clinton ’69 president. The political-science major was head of Wellesley Students for Hillary, and voters who spoke to her that day affirmed their intention to elect the first female president.

She, along with almost everyone on campus, was poised for a Clinton victory. “People were just ready to celebrate, wearing their Hillary gear, and alumnae were back on campus. So it felt like Wellesley was a lot more full than usual,” she says. And the energy was electric.

Students had organized several election night watch parties at places as varied as the Lulu Chow Wang Campus Center, Harambee House, and TZE. The Wellesley College Alumnae Association and the College had worked together to organize an alumnae watch event originally slated for Alumnae Hall. But when 3,000 women indicated they were returning to campus, from as far away as Australia, the staff created a larger event in the Towne Field House at the Keohane Sports Center. That eventually became a rallying place for students, too.

“I mean, you had everything from cupcakes to Hillary posters to the huge Jumbotron of the election [coverage] on CNN,” says Amber Walker ’17, who made the watch party rounds and ended up at the sports center. But after a few hours of election results, it became evident Clinton was losing, and Walker says attendees were hit by waves of disappointment and grief. “Nobody could really keep it together, I would say. Everybody began to break down,” she says.

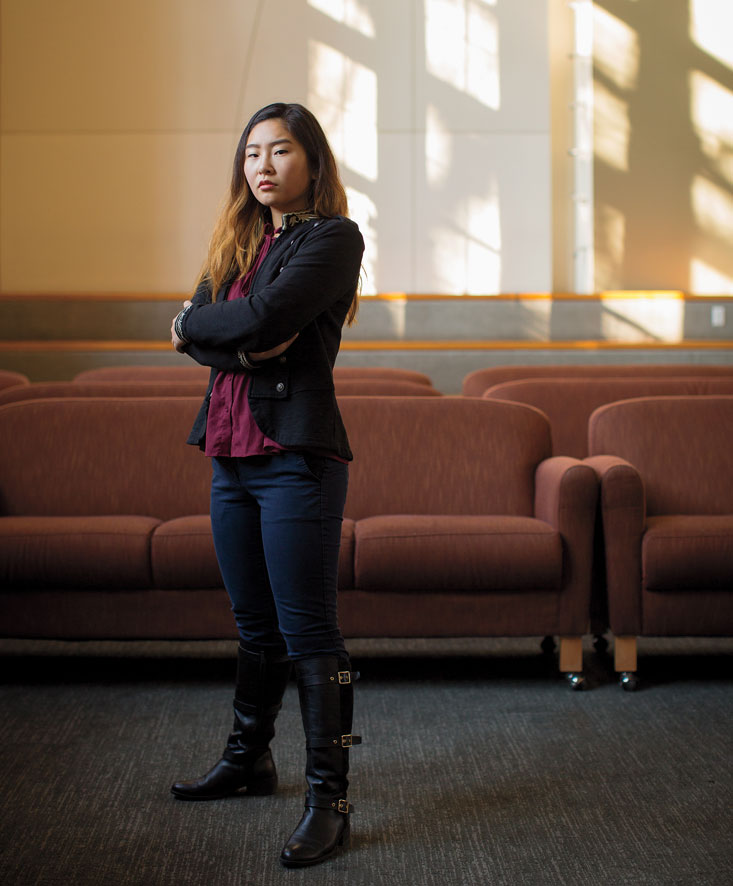

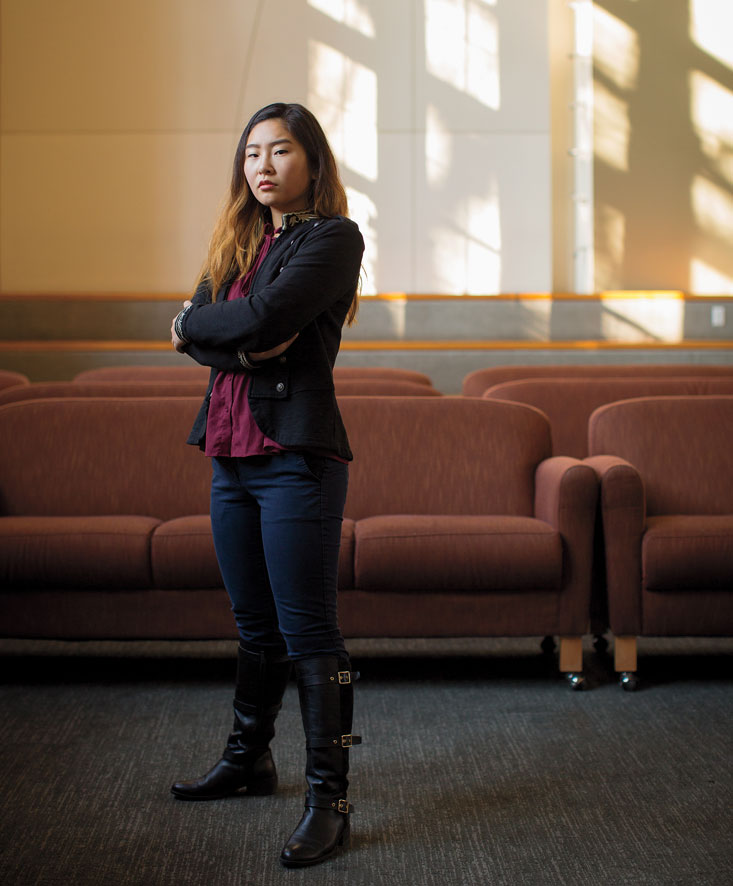

Karen Su ’19

Photo by Kathleen Dooher

Wellesley’s new president, Paula Johnson, had given a rousing welcoming speech at the start and now had to console at evening’s end. “I spoke to both alumnae and our students, to share with them that although this is not what we had hoped—to have one of our own becoming the first female president of the United States—our spirit is indomitable,” she says. “We believe in a path forward for every person, no matter your race, ethnicity, gender, religion, immigration status, or socioeconomic background, or quite frankly, your political affiliation.”

As difficult as it was, Johnson believes election night exemplified true community because Wellesley values are strong. “And I think it was an important moment for us all to be together and to share, and from that moment to start planning a different future,” she says.

The Day After: Eerie Silence

That future landed in the void of the following day. Most students and faculty hardly knew what to do. As Su says, “Someone really put it perfectly: I went to sleep to screams, and I woke up to an eerie silence.”

At the Multifaith Center in Houghton Chapel, Wednesdays happen to be dedicated to “A Place for Peace,” community time for discussing joys, concerns, or worries. Johnson was quick to call Tiffany Steinwert, dean of religious and spiritual life, who oversees seven chaplains across six different faith traditions and runs “A Place for Peace.” She asked if the dean could extend the regular program, and requested time to speak. Steinwert agreed, and the president invited the entire campus to attend.

Drawing together at the chapel, 100 participants heard from Steinwert that peace “does not mean to be in a place where there is no noise, trouble, or hard work. It means to be in the midst of these things and still feel calm in your heart.”

‘In many ways, it felt for our students as if the election was a referendum on themselves, a referendum on women and women leaders, and a referendum on their ability to impact and create positive change in the world.’

—Dean of Religious and Spiritual Life, Tiffany Steinwert

The sense of loss Steinwert witnessed did not just stem from an alumna’s defeat on the national stage. It was personal. “In many ways,” she says, “it felt for our students as if the election was a referendum on themselves, a referendum on women and women leaders, and a referendum on their ability to impact and create positive change in the world.”

While they listened to and discussed poems of pain, healing, and hope, two male students from neighboring Babson College were driving through campus in a pickup truck with a large Trump flag flying from the back, yelling, “Make America great again” and “Trump 2016.” (One of the Babson students confirmed these actions in an apology on Facebook on Nov. 11.) Swinging by the chapel, they ended up at Harambee House and then circled back. According to Chief Lisa Barbin, Campus Police stopped the truck just outside the Rt. 135 entrance and issued a verbal trespassing order, which barred the men from returning to campus until the order was lifted. The Wellesley town police also responded to the scene. Immediately afterward, the campus police at both Wellesley and Babson launched investigations.

Initial, secondhand comments on social media reported the Babson men were yelling racist and homophobic epithets as they pulled up to Harambee House, but according to the Boston Globe, which spoke to the attorneys of the men in the truck, Babson College’s investigation and hearing before its honor board showed no such evidence. (Babson itself—like all colleges and universities—is governed by federal law protecting student records and did not make a statement following the Dec. 19, 2016, hearing.)

Amber Walker ’17

Photo by Kathleen Dooher

Amber Walker was at Harambee House when the incident happened, and reported the activity to Campus Police. What disturbed her was that it felt like an effort to intimidate. “I’m originally from Atlanta, so you know, I’ve seen and heard a lot of racist and bigoted things, to say the least. So when I saw this Trump truck, what was most alarming for me was ‘Wow, wait, I’m in Wellesley, Mass. I haven’t seen someone try to come up and threaten, just with their presence, my existence in this town.’”

Walker says the Babson students did not call her out or tell her anything racist, but as the truck moved slowly along, and they were chanting, “Trump, Trump, Trump,” it felt to her as if they were making a statement to students of African descent.

Word about the Babson students’ drive flashed through social media.

A Call to Action

Alexa Rodriguez ’17 was off campus, but received a text from her boss at her campus job, asking her if she was OK. Her employer’s message about the incident was jarring. “I’d read about these things happening, but it’s another thing to have them happen in your home.” It made her fearful. “It would seem that I live in a country that I didn’t know I lived in. I myself was afraid because I’m a person of color, low socioeconomic status, so definitely not a majority here. We just felt really small on those days following,” she says.

Amina Ziad ’17 found out on Facebook, and she, too, was shocked. “I think my shock stems from the fact that stuff like that doesn’t happen at Wellesley. You know, we don’t treat each other that way,” she says.

President Johnson understood how vulnerable students felt, especially when election sentiments were raw, and the campus, which had felt protective, no longer did. So she called for a peace walk to reclaim Wellesley’s spaces, and on Nov. 11, she linked arms with students, faculty, and staff, and a line of hundreds of people snaked through the campus, ending up at the lake.

“When we are feeling vulnerable because there’s some sense that we are at risk because of who we are, the best way to face that fear is through recognizing our power to participate actively in our democracy,” Johnson says.

Rodriguez and Ziad had been discussing how it was not enough for them to mope or post on social media. They had to act. “This is a call to action for everyone within this community to stand up when they have the privilege to do so, and to speak up when they have the opportunity to do so,” Ziad says.

‘When we are feeling vulnerable because there’s some sense that we are at risk because of who we are, the best way to face that fear is through recognizing our power to participate actively in our democracy.’

—President Paula Johnson

She, Rodriguez, and other students went to work, figuring out what they would need to do to organize a march from campus into the town of Wellesley, plus ask various Babson students to participate, and have students from both campuses speak. They contacted Dean Steinwert, an experienced community organizer, to guide them in the complicated logistics of constructing a peaceful march and moving it off campus. And on Nov. 16, they pulled it off: Their invitation read, “Walk with us. Stand with us. We are still here. This is our home. We belong here.” Approximately 250 people marched to protest hatred and bigotry, and Babson students met Wellesley students at Morton Park, halfway between their campus and the College.

Alexandria Otero ’19, who was in charge of communicating with campus police and the town of Wellesley, is proud of the end result. The vision was the students’, but they felt supported by faculty and staff. She notes that the Office for Religious and Spiritual Life even provided buses to return students to campus in time for classes.

Steinwert believes the rally was energizing for students. “I think it was a wonderful way for students to transform their grief in a way that was visible and powerful, and made them feel like they had agency, even in the midst of a world that no longer felt like it made sense.”

Conservatives on Campus

The election affected American studies major Lauren Keena ’17 in a different way. She is president of the Wellesley College Republicans and says the season was tough for conservative students. “While it was wonderful to see a Wellesley alum in such a high position, and as much as I wanted to support the candidate, I couldn’t,” she says. “What was hard for conservative students was trying to juggle a love of Wellesley and political affiliation.”

But she points out that neither she nor other Republican students felt vindicated by the election results. “I couldn’t really be all that happy because so many of my peers were completely and utterly heartbroken, and it’s very hard to see politics play out in a way that you might favor, knowing so many people you interact with day to day are very unhappy,” she says.

She, too, believes the Babson incident deepened the wounded feelings on campus. She was at “A Place for Peace” when the truck was making its way through campus. “I had just come out of this uplifting community togetherness moment, and walked outside the chapel only to hear that people were hurting even more than before, which was strange for me in that I had been with people who had taken steps to move forward. And it felt like we were sort of knocked backward,” she says.

In the days ahead, her group will cohost events with Wellesley College Democrats and College Government’s Committee for Political and Legislative Awareness. “The goal is just to encourage open political discussion, to break out of the echo-chamber mentality,” she says.

Lauren Keena ’17

Photo by Kathleen Dooher

A Community Learning Together

Immediately after the election, faculty organized panel discussions to reflect on voting outcomes and the political climate, drawing on their research specialties. One gathering was sponsored by the Department of Political Science and another by professors from various social-science departments. In addition, the Office of the Provost issued a call for two teach-ins, which were attended by overflow crowds on Nov. 18 and 29. These were cross-disciplinary discussions and allowed for extensive questions and answers with students.

One of the teach-in scholars was Assistant Professor Angela Bahns, a social psychologist whose research focuses on similarity and diversity in friendships, and on how prejudice develops. After observing the vitriol characterizing the election, she told students that people will openly express prejudices they believe are acceptable to most. “So the most immediate way to help stop these acts of prejudice is to create a tangible social norm that hatred will not be tolerated,” she says.

She asks students to look for underlying causes. “One of my goals is getting students to recognize that we all have bias. One of the big ideas guiding my research program is that it’s important to get to know people who are different from us. I think diversity of thought is undervalued and infrequent in practice, and there’s great benefit in getting to know people who we do disagree with,” she says.

Brenna Greer, Knafel Assistant Professor of Social Sciences and assistant professor of history, also participated in a teach-in. She is a historian of race, gender, and culture in the 20th century, with a focus on African-American business and visual culture. She was teaching the morning after the election, and opened up her class for discussion. She says her students—though upset and frightened, including some Muslim students who were concerned for their families’ safety—made her hopeful. “It made me feel good that they were upset and that they wanted to address it,” she says. She explained to her class that in history there are patterns of progress: “There’s a huge push, crushing backlash, and measurable change.”

But from her perspective, what has been lacking are discussions about race, even during the Obama presidency. “We never had the discussions about race, or took that on—racism in particular—in a way that would have made what’s happening now impossible,” she says. “We can’t have the conversations that are necessary to talk about institutionalized racism, which you have to do to be able to undo some of the things that we’re experiencing.” So she is promoting dialogue about the topic.

On Nov. 11, President Paula Johnson led students, faculty, and staff on a peace walk through the campus.

Photo of Wellesley students at the Nov. 18 protest march.

Students organized a protest march against hatred and bigotry through the town of Wellesley on Nov. 18. They were joined by students from Babson College.

For Johnson, the way forward is to reinforce Wellesley’s rigorous liberal-arts education. “What we stand for at Wellesley is scholarship and teaching in search of the truth. And as we navigate that path of history and interpretation, that it’s based in fact, and not in pure emotion or what we want to believe,” she says.

Many credit Johnson for rapidly changing the tenor on campus to allow students to get back on track after the election. She helped coalesce students, faculty, and staff with actions that made them feel purposeful, and for those who felt fear, to feel more empowered—be that through peaceful meditations, marches, teach-ins, or convening a town hall on immigration to provide clarifications about the law while presidential administrations shift.

As students examine what it means for women to lead, Johnson believes alumnae play a critical role. “Your commitment to our current students, your commitment to each other and women in the world is extraordinary,” she says.

Students agree. Amber Walker says it’s important for her to hear from multigenerational voices expressing different experiences. Lauren Keena appreciates the alumnae who let her know there is an ebb and flow to politics, and Alexa Rodriguez is heartened by the alumnae who went on the town march. “You hear about the Wellesley network; it takes on a mythic reality. You know it exists, you hear about it, but you really don’t know until you get your hands deep into it,” Rodriguez says.

Although Babson College has not made a public statement about disciplinary actions for its two students who drove though Wellesley, the Boston Globe reported on Dec. 19 that they were cleared of accusations of harassment and disorderly conduct. It’s also important to note that on Nov. 10, Babson’s president, Kerry Healey, apologized to the Wellesley College community for the students’ behavior.

Johnson says Wellesley needs to honor what its students experienced and “use that experience to again mobilize us to work even harder for our values and for the future we want to create.” The incident, she adds, is “a call to action.”

Yolette García ’77 is an assistant dean at Southern Methodist University’s Simmons School of Education and Human Development. A former longtime public broadcaster, she oversaw news and public affairs for radio and TV at KERA in Dallas.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.