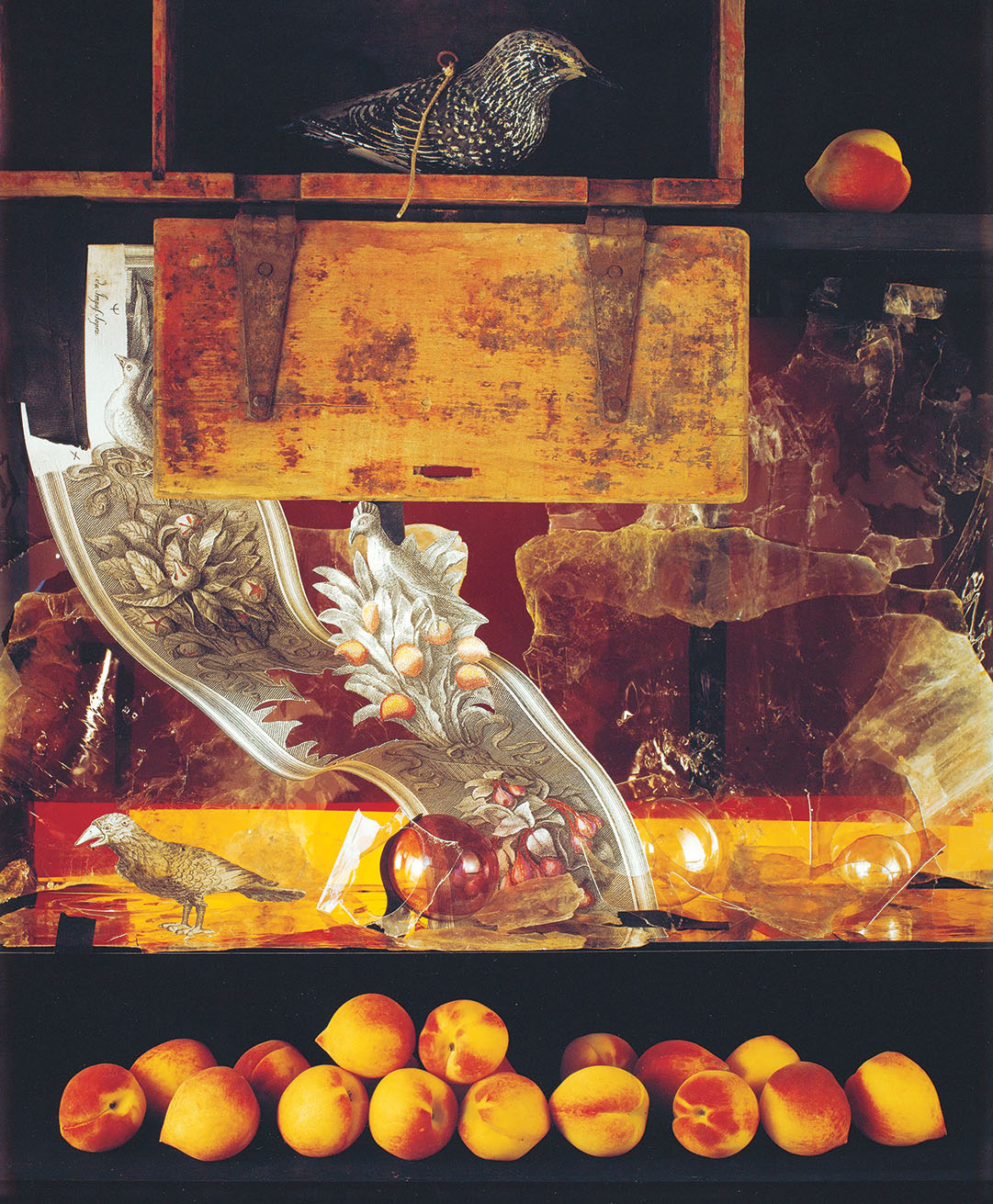

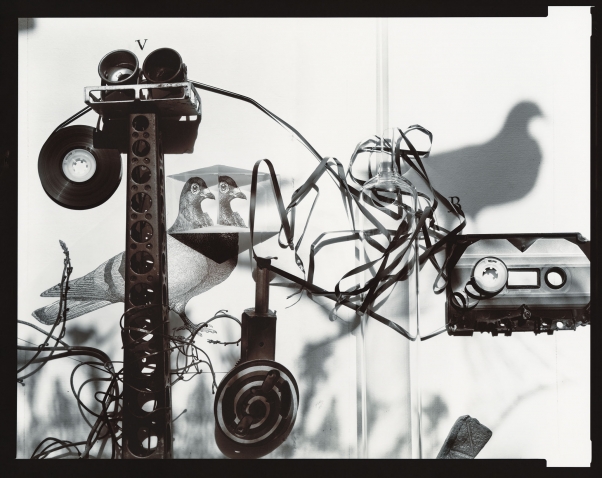

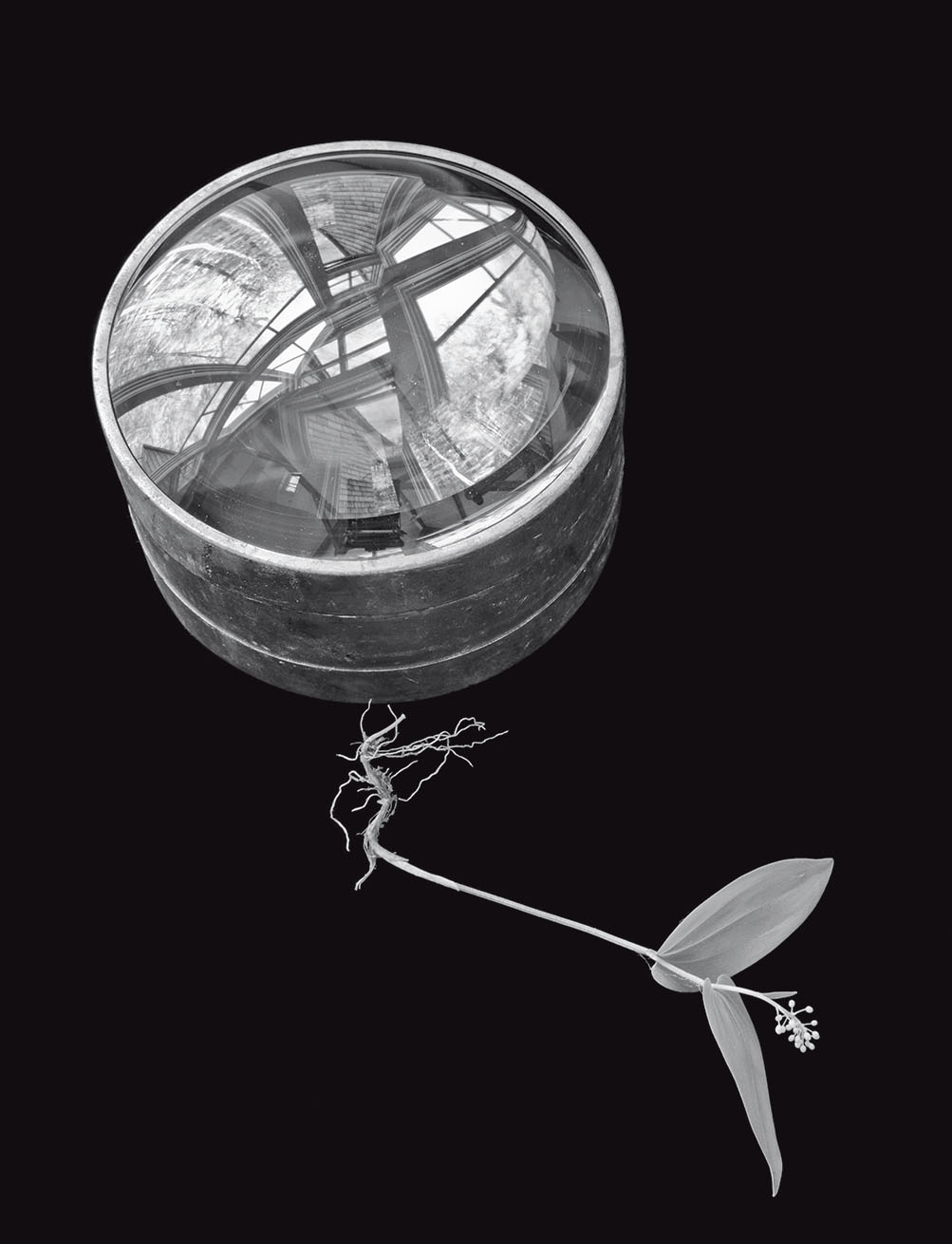

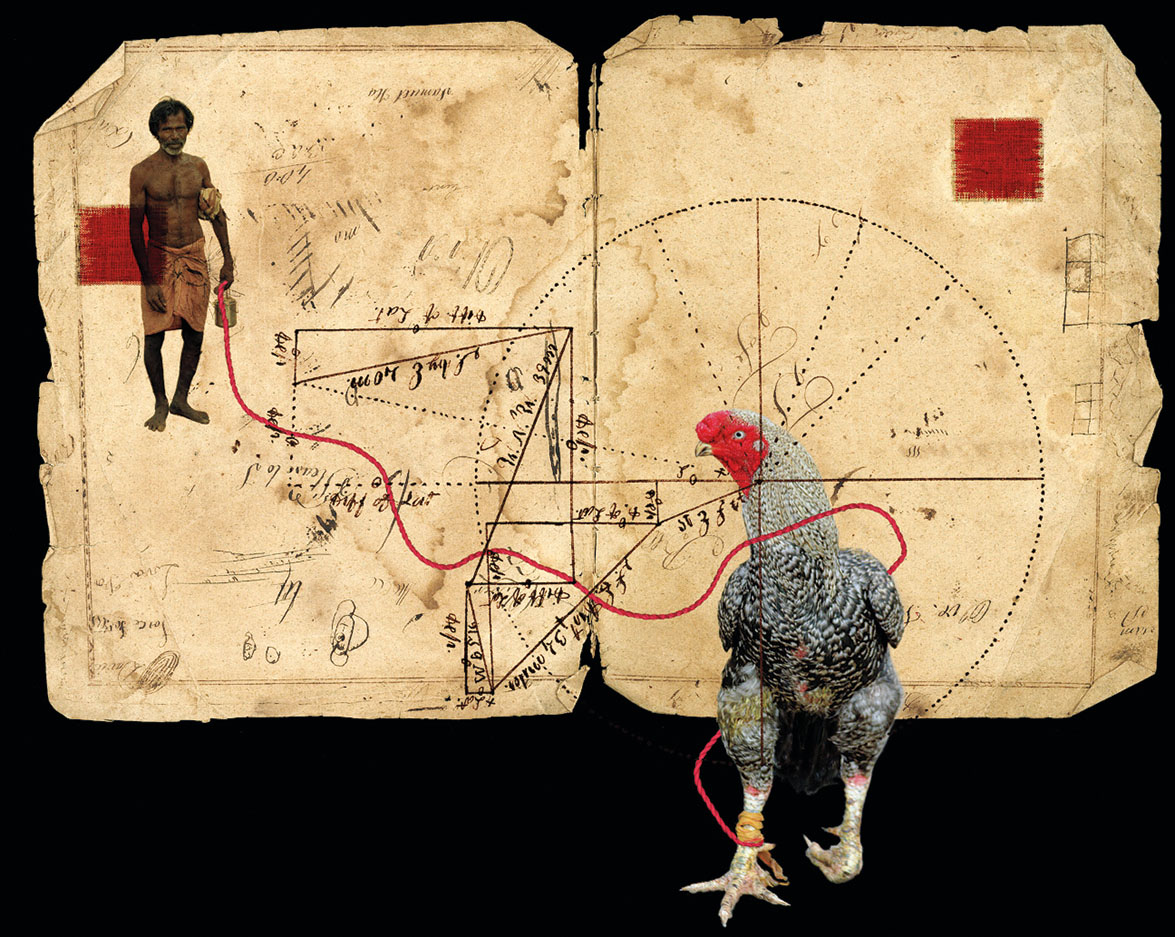

Feral Tape, 1984, gelatin silver print, 11 in. by 13 ½ in.

For photographer Olivia Hood Parker ’63, a beautiful or evocative object seizes her imagination regardless of its origins. In 2012, her plumber was replacing the leaky rubber flappers in her toilet tanks. He was preparing to throw the old ones away, but Parker stopped him. Her attention was captured by the gorgeous blue-green corrosion on the old parts, which reminded her of ancient bronze sculpture. With an eye toward a future photograph in which she might pair the flappers with Chinese bronze sword hilts from the second century B.C.E., she rescued them from the trash.

“Olivia sees the potential in coupling [plumbing parts] with these Chinese treasures,” says Sarah Kennel, Keogh Family Curator of Photography at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, who organized the recent retrospective, Order of Imagination: The Photographs of Olivia Parker, at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass. “This points to her two sides: her long interest in history but also her interest in the material world and finding things in unexpected places.”

In a visit to Parker’s spacious, window-wrapped studio north of Boston, you encounter a cabinet of curiosities: trays of shells and bones, cast-off mechanical parts and pieces of scientific equipment, old maps and charts, glass prisms and shards of twisted metal. In an order known only to Parker, objects are stored in horizontal filing cabinets, and still others occupy nearly every remaining horizontal surface. They have been the raw material of Parker’s art for more than 50 years, part of what Kennel has described as Parker’s “magpie aesthetic.”

From an early age, Parker enjoyed going out into nature and bringing back objects that she arranged in old shoeboxes. She possessed a talent for drawing and painting and had wanted to attend the Rhode Island School of Design, but her parents urged her to go to Wellesley. Originally, Parker had planned to major in science, but she chose to study art history instead. The coursework steeped her in a rich curriculum that included historic methods of making art, as well as the history of genres such as still life. As she pursued her painting, she retained a scientist’s curiosity.

“In any kind of art, you’re experimenting,” she says. “You want to see what will happen if … . It’s the same in science. For anything to get done, you have to go off the edge of the map. The hope is finding something in that uncharted territory.”

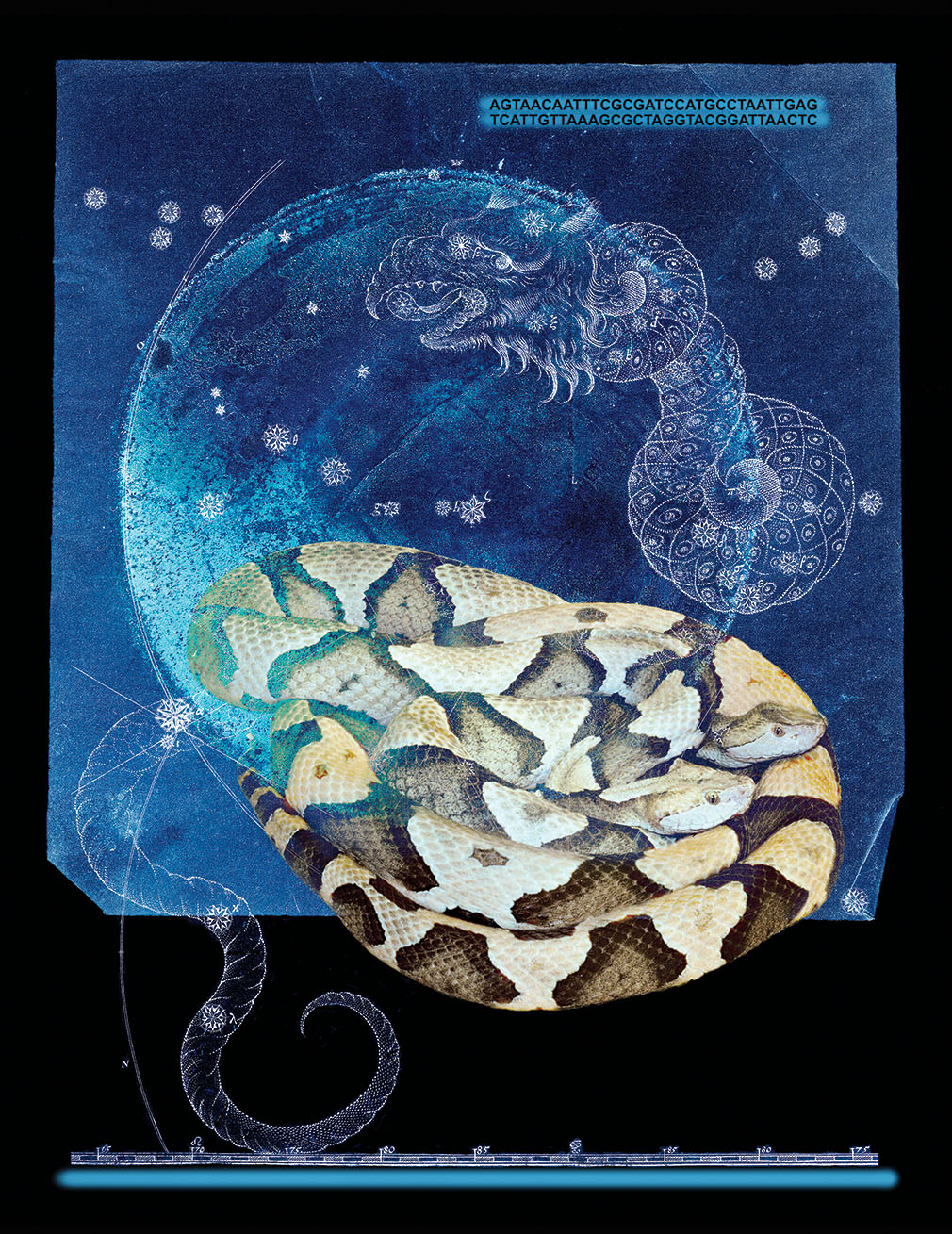

Parker, who received an Alumnae Achievement Award in 1996, draws inspiration from plunging into unknown territory. Her photographs speak of strange and wonderful juxtapositions, invented worlds, and moments of transition. She’s interested in processes and instances of flux, such as dishes and flowers falling from collapsing shelves, or a piece of fruit changing from over-ripeness to decay. Her photography appears in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, among others. This past November, she was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame.

Parker in her studio in Essex, Mass., with poodle Rover

Photo by Bob Packert/Peabody Essex Museum

Parker’s methods involve photographing a group of objects in the studio or natural phenomena in the field and layering or manipulating the images to achieve the final photograph. She might set up a shoot by arranging objects on the floor, for example, paying close attention to the natural light flooding through the windows. She frequently places clear or colored glass bottles in the path of the light, which lends a wavering, otherworldly appearance.

The evolution of her career has been marked by what curator Sarah Kennel characterizes as a “sustained engagement with the history of art, a keen sensitivity to light and composition, and a willingness to experiment with photographic technique.”

Parker began her artistic career as a painter, but in the early 1970s, she shifted to photography, making assemblages of natural and human-made elements that she combined with Merlin-like skill into photographs that hinted at shadowy worlds and strange truths. She also explored beyond the reaches of what was then accepted practice in the darkroom. For example, she exploited the possibilities of split-toned prints, in which a print is left in the toner for a longer length of time.

Parker liked the more painterly quality that split-toning gave her prints: The black and white images developed areas of warm browns and cool blues. Her work even managed to win over Ansel Adams, the authority on all things photographic, who had earlier decreed that split-toning created an “unpleasant effect.” He eventually invited her to teach at his workshops in Yosemite.

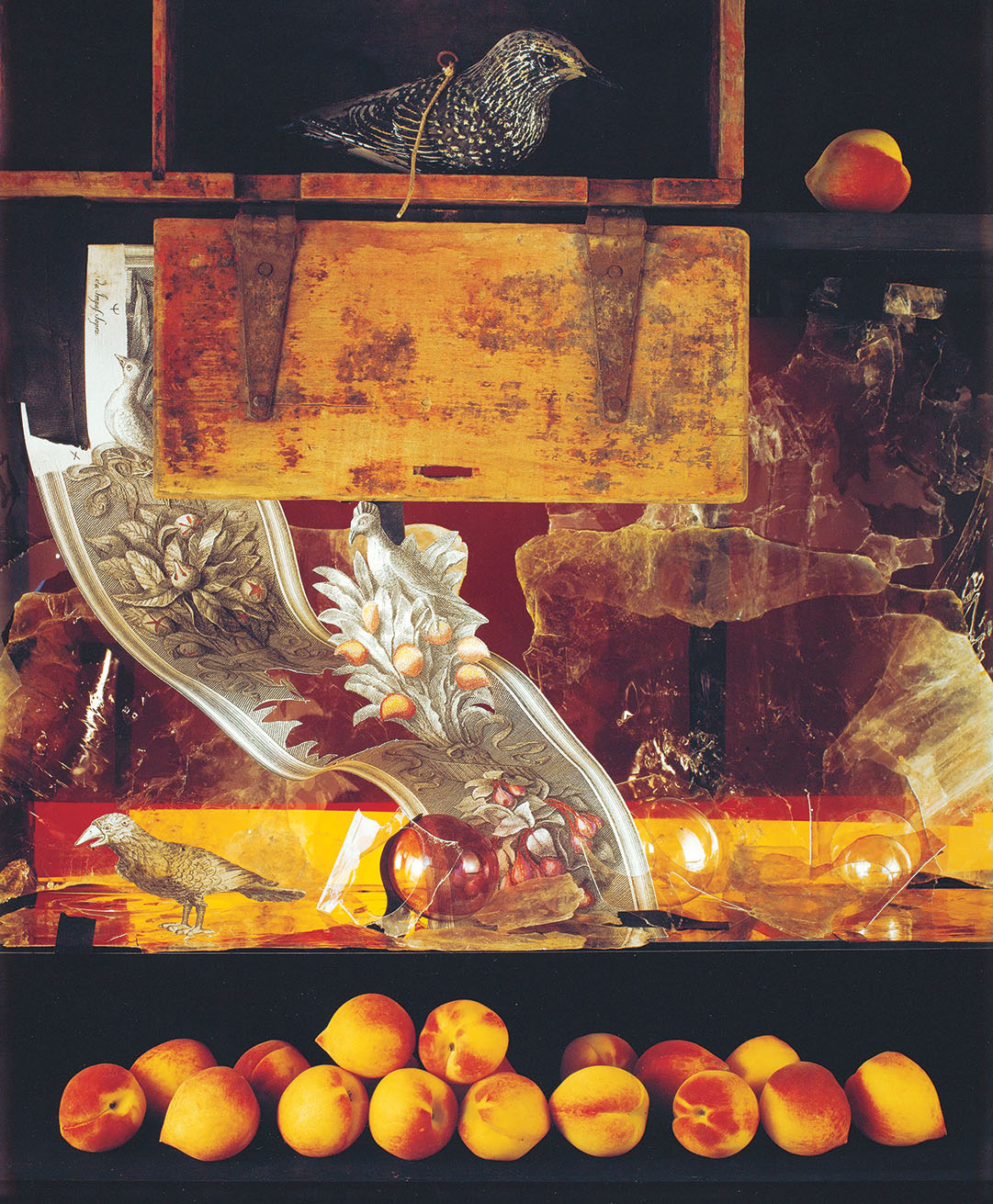

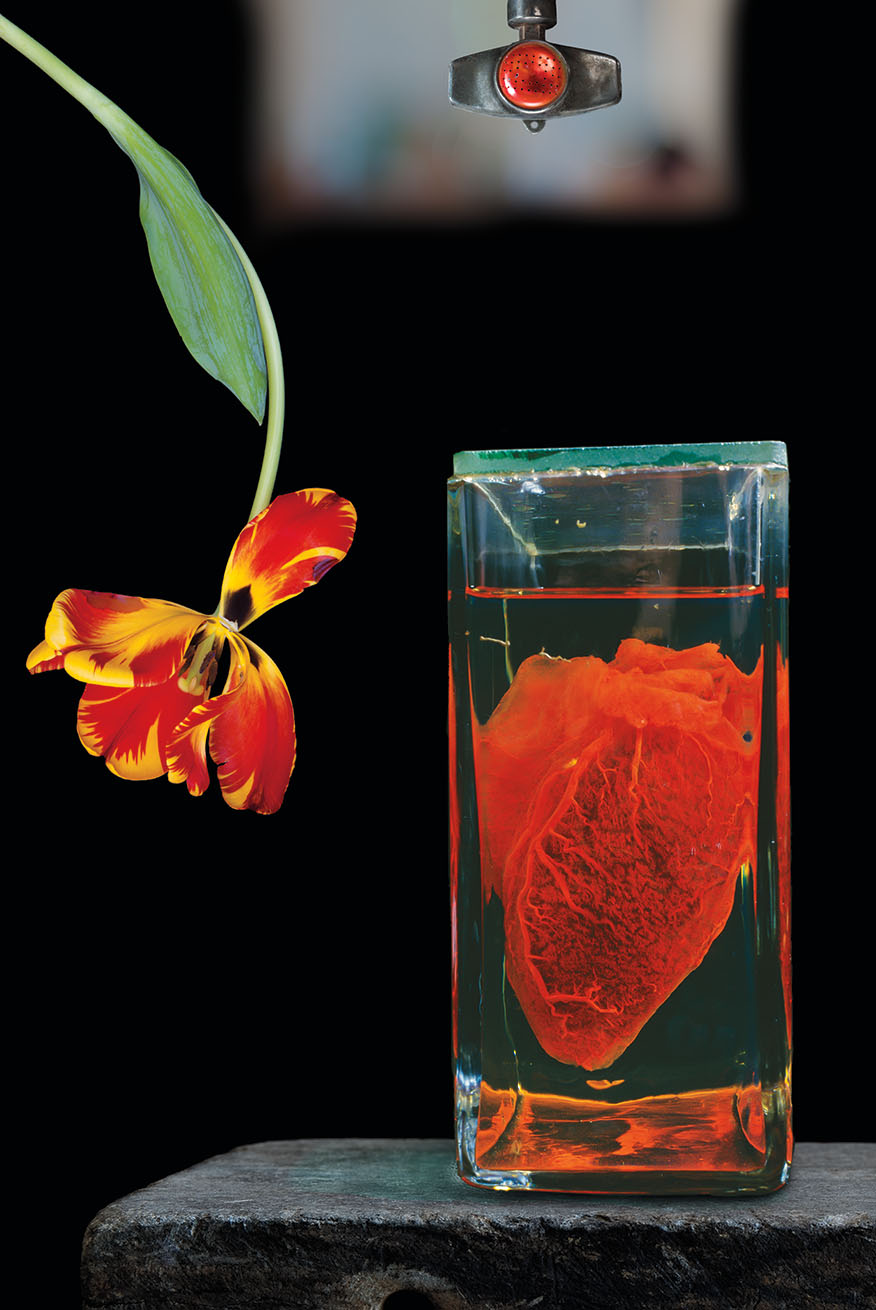

Interior with Birds and Peaches, 1981, dye diffusion print (Polaroid), 30 ¾ in. by 22 in.

In the late ’70s, she was one of the many artists invited by the Polaroid Corporation to test its products. Over more than 10 years, she explored the possibilities of Polacolor instant color film. During this time, she created ravishing still lifes that in their color saturation and subject matter recall 17th- and 18th-century Dutch masterpieces, but with her own twists.

“A painter is in control of her canvas in a way few photographers are,” says Henry Horenstein, a photographer and professor at the Rhode Island School of Design who has known Parker for five decades. “Most of us have to deal with what’s given, what’s out there, and make that fit to our vision. Libby constructs her images more like a painter than most photographers.”

Parker’s professional career evolved alongside her role as a wife and mother. After graduating from Wellesley, she married John Parker in 1964. The couple welcomed their first child in 1967, and their second two years later. The family lived in a rambling summer home perched on a cliff overlooking the Atlantic in Massachusetts, and Parker carved out studio space in the living room and in a glassed-in porch.

Kennel says, “The implicit family expectations made her more committed to figuring out a way to work,” whether that meant working at home, a mom’s day out shooting photos in a graveyard, or creating a community with other artists in the area.

“The challenge of making art when raising a family—that was something that I just kept working at,” Parker says. “Fortunately, despite the teasing, my family was sympathetic.” Her children’s friends, she says with a smile, called her “weird mom.”

Each challenge Parker faced seemed to become a catalyst for the next step in her growth as an artist. When she broke her leg in a 1995 skiing accident and was confined to the house for a year to recuperate, she learned Adobe Photoshop. “She was one of the earliest [fine-art] photographers to adopt digital cameras,” says Kennel. The medium of digital photography and the ability to store endless numbers of images were a boon to Parker’s subsequent work.

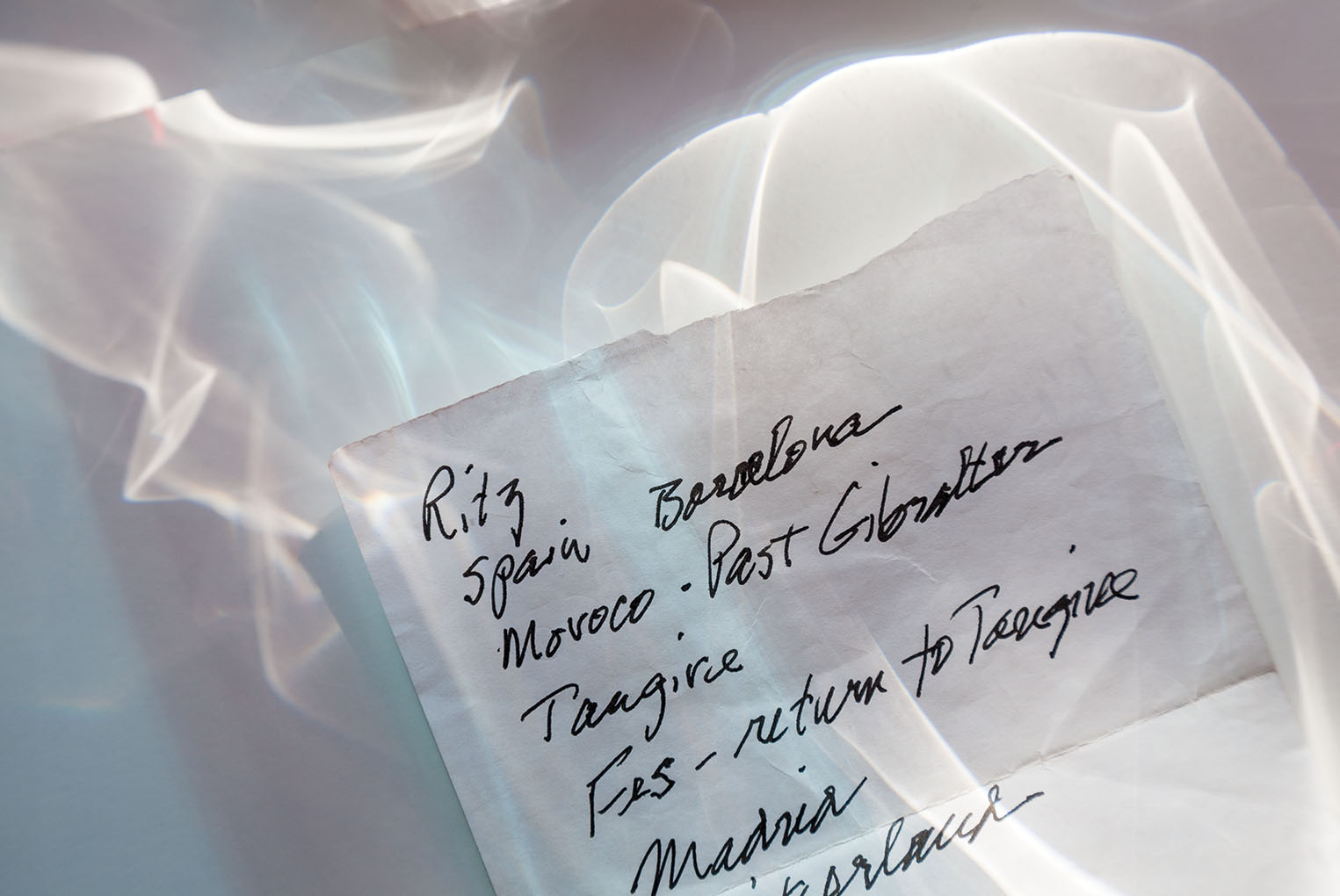

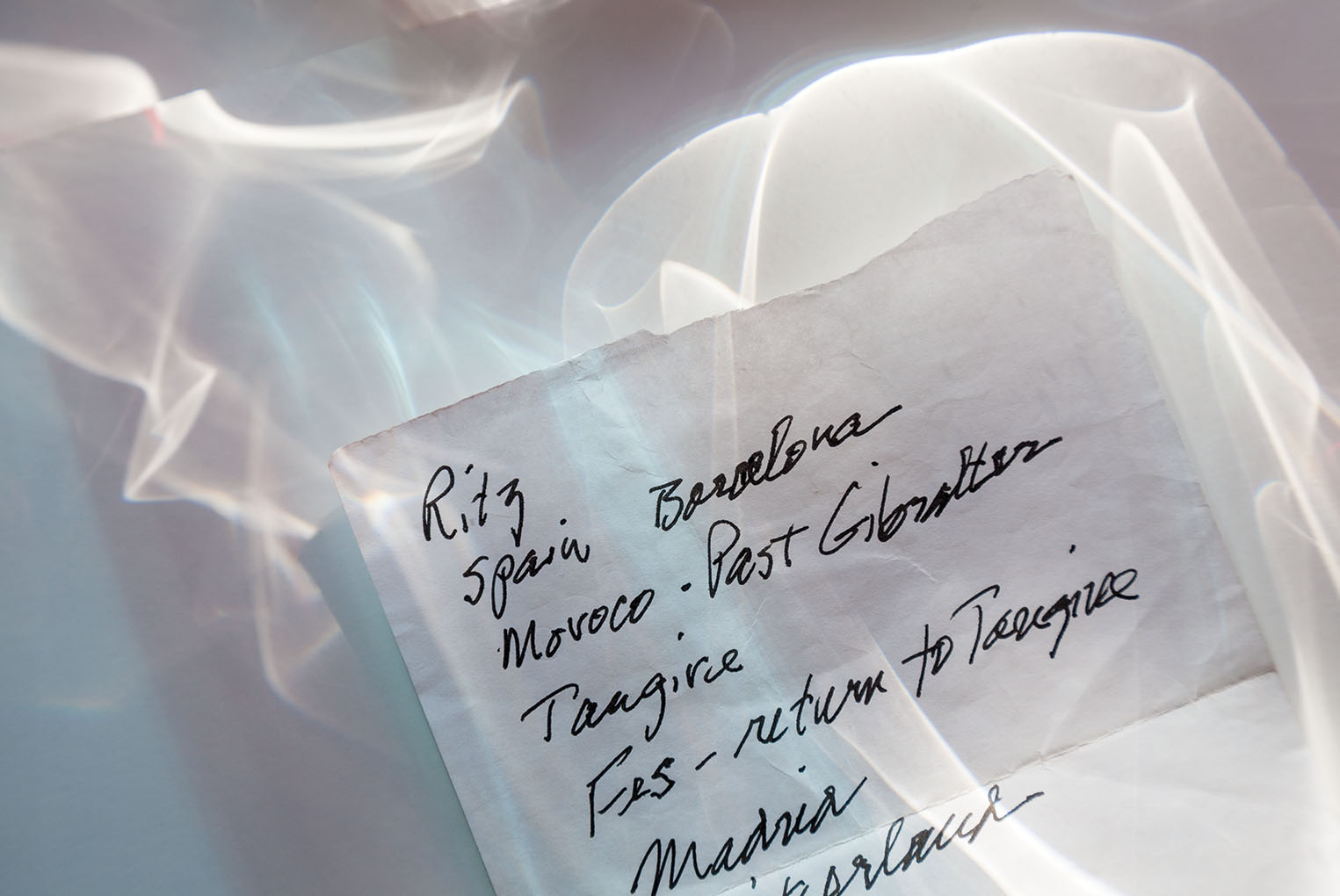

Honeymoon, 2016, inkjet print, 14 ⅝ in. by 22 in., part of the “Vanishing in Plain Sight” series

But her truly defining challenge came in the form of her husband’s illness. In 2013, John, a financial analyst with a great interest in the arts and education, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Shortly after his diagnosis, Parker was shown a scan of his brain. “I was shocked. There were huge black areas. It looked like there was nothing left at all,” she says. But he was in denial about his condition. “He said to me, ‘Please don’t tell anyone that I’m ill,’” Parker says. “Other people would have looked for drug trials to stave off the disease, but he never even said the word Alzheimer’s. His neurologist had him write the word down and spelled it for him.”

She began researching the disease and attempting to manage her husband’s changing personality and increasingly unpredictable and often violent outbursts. She tried to imagine what John was going through. After the difficult decision was made to move him to a care facility, Parker found stacks of notes on which he had written things he did not want to forget, including names of friends, and, most poignantly, the places he and Parker had visited on their honeymoon.

Parker began to photograph not only the detritus of her husband’s life—the digital watch he could no longer use, the zippers and fasteners he could no longer manipulate, the reminder notes—but also to imagine what it was like to be John. To see with his eyes.

The resulting photographs in the ongoing “Vanishing in Plain Sight” series are her “most painterly,” according to both Kennel and Horenstein. The liquid effects of light, the blurred edges of mysterious origins, the fragmenting of forms into diminishing planes, these hint at the tremendous changes taking place in John’s mind.

“She’s honoring a 50-year marriage with the deepest form of empathy,” Kennel says.

John died in 2016, just before Parker started working with Kennel on the retrospective. The exhibition, which closed last November, was planned so that the viewer moved chronologically through Parker’s work, concluding with selections from “Vanishing in Plain Sight.” But Parker didn’t want the exhibition to end on such a somber note. Instead, a large screen played a video of Parker in her studio, light pouring in, demonstrating how she works. It’s the place she clearly feels most at home, and the continuity of that image provided a satisfying note on which to end the exhibition.

When asked what has kept her going through all the challenges, Parker points to her desire to keep experimenting and see where things go. She says simply, “I just really like to work, to see what will happen if … .”

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.