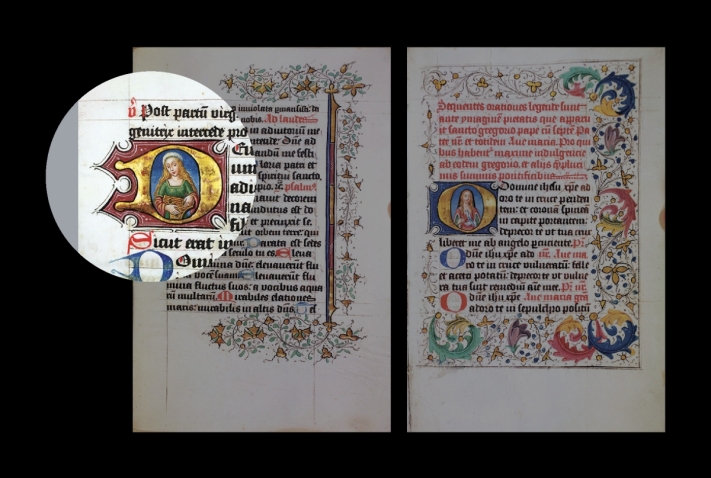

This saint’s twisted, contrapposto posture, not typical of Renaissance paintings, tipped off a medieval manuscript expert that she might be fake. Photo courtesy of Wellesley College Special Collections

On a Sunday morning last May, Ruth Rogers, curator of Special Collections at Wellesley, sat down to enjoy one of her favorite medieval manuscript blogs, and was shocked to discover a post about two Books of Hours in Wellesley’s collection—Manuscript 27 and Manuscript 29.

The blog’s author, Peter J. Kidd, a London-based medieval manuscripts expert, wrote that he doubted the authenticity of parts of those two books, which he had examined prior to an exhibition of illuminated manuscripts in Boston in 2016. Further, he wondered if some of the illustrations were created by the Spanish Forger, who painted numerous miniatures and panels in a late-medieval style in the late 19th century and into the 20th century. The forger boosted the value of manuscripts by adding sought-after illustrations. Kidd thought that in Wellesley’s Manuscript 29, for example, there were several historiated initials—an initial that begins a section of the manuscript and includes an illustration—that looked wrong. The poses of the characters in the illustrations are not typical of the period, Kidd wrote, and the context in which they appear is often “bizarre.”

Rogers was surprised, but also intrigued and excited. She arranged to take Manuscript 29, a Book of Hours from the late-15th-/early-16th-century that was written and decorated in the Northern Netherlands, to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston for X-ray fluorescence testing. (Manuscript 27 sat the trip out.)

In August, Rogers and codicologist Lisa Fagin Davis, who originally catalogued the College’s collection of pre-1600 manuscripts in 2001, and Emily Bell, the College’s collections conservator, traveled to the MFA’s conservation lab with the book. Rogers and Davis selected targets for testing, focusing on reds, blues, and greens. They selected miniatures that were likely original to be scanned as a baseline, and those that were suspect were scanned for comparison.

The results were immediate and obvious. Each of the three suspicious initials had noticeable levels of arsenic in the green paint, a telltale signature of “Scheele’s Green,” a pigment first manufactured in 1775.

“It just adds another layer of history that we didn’t know. If anything, the combination of art connoisseurship and technology we used to find the truth, I think makes [the manuscript] far more interesting,” says Rogers. She uses this particular manuscript frequently when classes visit Special Collections, or when teaching her own course on the history of the book. Now she has a fuller story to tell about it.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.