When art historian Rachael Arauz ’91 began searching through library archives and attics full of dusty bankers boxers to mount a major museum exhibition about the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, she was hoping to uncover the origins of the school, unique in North America for bringing together artists and amateurs from a variety of media—fiber, ceramics, metal, wood, glass—for an intense summer experience of art-making, experimentation, and community in rural Maine. What she hadn’t expected to discover was a Wellesley connection. But there in a 1951 newspaper profile of one of the school’s founders, Elizabeth Crawford 1921, was a reference to her attending Wellesley College. “Beth Crawford had really just been lost to history,” says Rachael.

In the exhibition for the Portland Museum of Art In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950–69, Rachael and her co-curator, Diana Greenwold, tell the story of Haystack’s founding by a small group of friends and fellow artists—Crawford among them. Crawford had a long career as a college librarian before taking up pottery, first as a hobby, then as a passion. In the 1940s, she moved to a small cottage in the Maine woods to devote herself to her art and creating the artistic community that would become the craft school. “She represents a very typical story of women finding their way in a career, then discovering a different version of themselves at a different point in life,” says Rachael. “Women don’t always have a quick and easy path to an unconventional life.”

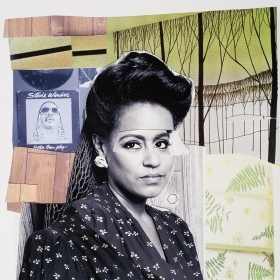

Elizabeth Crawford 1921 (left, in plaid shirt) at Haystack’s pottery studio in 1951

Rachael is familiar with the conventional path that veers into new territory. Since her first exposure to art history at Wellesley, she has been committed to a curatorial career. After graduation, she did the expected thing: an internship at the National Gallery, a Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania. She taught for a few years, first at Williams College and later at Wellesley (2001–02). But then, through several twists of fate, she was hired to work as the curator of a very large private art collection in the town of Wellesley.

“What I thought was going to be a quick little job while I had a baby at home, I’ve now been at for 13 years,” she says. Rachael and her husband, a working artist, now have two children, ages 11 and 14, and she credits that job with allowing her to support their family, be home with their kids, and curate a number of exhibitions at museums from Maine to Mexico City. “It has enabled us to build a quirky, unconventional model of life that is oriented around art and creative work and being part of creative communities,” she says.

Like Crawford, Rachael has labored to build up artistic communities. A few years ago, she started a collaboration with Wellesley’s art department where students visit the collection she curates along with artists whose work is there. Now, she is fund-raising to establish a scholarship in honor of Crawford so that a Wellesley alumna can attend Haystack every summer. Unlike other 20th-century experiments in utopian artistic communities, Haystack survives. “They are thriving,” says Rachael. And by helping send alumnae to Haystack, she hopes to help other women discover the spirit of art and community that Crawford helped create.

In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950–1969, is traveling to the Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., where it will be on view from Dec. 14, 2019–March 8, 2020.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.