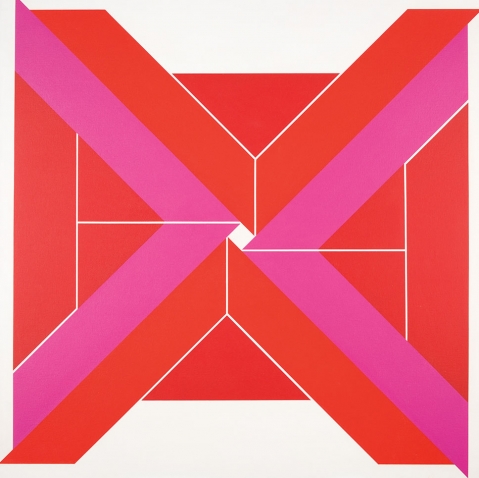

Elaine Lustig Cohen, Inward Longing, 1967, Acrylic on canvas, 50 by 50 in., Museum purchase, Erna Bottigheimer Sands (Class of 1929) Art Acquisition Fund, 2016.4

Courtesy of the Estate of Elaine Lustig Cohen

Elaine Lustig Cohen (1927–2016) was an accomplished graphic designer when she painted Inward Longing in 1967. Best known for her pathbreaking freelance career in the 1950s and 1960s in the male-dominated field of graphic design, Cohen created hundreds of book covers for clients such as Meridian Books and New Directions, while also parenting her young daughter.

Soon after completing a B.F.A. at the University of Southern California, she married acclaimed designer Alvin Lustig, and acquired her own sharp eye for design under his supportive tutelage. Following Lustig’s untimely death, when Elaine was just 28, his clients welcomed her ability to take over his projects, and her independent career was born. In 1956, she married publisher Arthur Cohen, with whom she later founded Ex Libris, a unique bookstore and gallery on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

Cohen’s creativity thrived at the intersection of art, architecture, and design. Among her most important early clients was architect Philip Johnson, who asked her to fulfill Lustig’s commission to create signage for the now-iconic Seagram Building on Park Avenue. Her award-winning typeface remains a key aspect of the building’s identity. For the Jewish Museum in New York, Cohen helped define its progressive identity in the mid-1960s with a series of spare, bright designs for catalogues, including the important 1966 exhibition Primary Structures. Cohen’s personal and professional connections to a broad community of artistic, intellectual colleagues nurtured her unusual career, and provide an important context for her paintings.

Inward Longing is among a number of early paintings Cohen created as she began to shift away from design commissions and to prioritize making art. The large square composition features an array of trapezoids, in deep pinks and bright reds, that converge, but remain just out of alignment, to articulate a small, bright white square at the center of the canvas. Darker red triangles and trapezoids fill the four sides of the X, intensifying the compressed sensibility of the geometric forms. Using tape to mask paint fields as she worked, Cohen defined sharp edges between the hot colors, and created thin white lines to draw the viewer’s eye around the arrangement of shapes and toward the central, rotated square. Deceptively simple in its flat planes of acrylic paint and simple geometry, Cohen’s work masterfully confounds the stability of the square canvas with a dynamic and vibrant composition that achieves a sense of movement.

In 2015, shortly before Cohen passed away, her paintings were exhibited at Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Conn., and an interview with the artist was published in Artforum. Cohen remarked, “My abstraction never came from narrative; it came from architecture.” Produced at a key moment in Cohen’s career, and distinct from American midcentury art movements such as abstract expressionism, pop art, and minimalism, Inward Longing represents an important, alternative aesthetic vocabulary of color and shape informed by a broad design sensibility. The recent addition of Cohen’s work to the Davis Museum collection enriches the complicated story of modern art Wellesley students will see and learn.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.