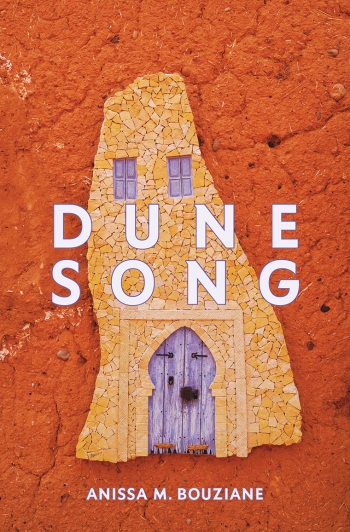

Dune Song, the debut novel by Anissa Bouziane ’87, shares the spiritual and physical journey of Jeehan Nathaar, a Moroccan-American Muslim woman who seeks healing and affirmation of her identity and purpose after witnessing the 9/11 terrorist attack in New York City. Published first in French in Casablanca in 2017 and recently released in the U.S., the story is told in alternating chapters between New York and Morocco as Jeehan moves through an epic journey of self-discovery, finally finding peace in the deserts of her father’s homeland.

Before 9/11, Jeehan was at a crossroads. Her Ph.D. advisor had passed away before she could complete her history dissertation, and she lacked funding to continue. Living in New York with her sister, Rizzy, a photojournalist who finds purpose traveling around the globe capturing important world events, Jeehan is passing the time working as a paralegal to pay rent.

It seemed this aimless path could continue indefinitely, until the falling of the World Trade Center towers. Jeehan sees the first tower crumble before her eyes and is deeply affected. The event and its aftermath shift her world perspective. She had always thought “that death on this scale, with this level of collective violence, with the capacity to touch so many people … belonged to older continents.”

The 9/11 attack is more than a catalyst for Jeehan: It fundamentally changes the way she is able to navigate the world and how people see her. She experiences Islamophobia and xenophobia at work and social gatherings. She’s eventually let go from her job, and it’s clear that she can no longer continue living invisibly. 9/11 had left a “scar that would be permanent.”

Jobless and still processing without direction or many resources, Jeehan reconnects with Ali, a former roommate and lover. They discuss traveling to the Moroccan dunes to work on a story about human trafficking of migrants crossing the desert. But Ali fails to materialize at Casablanca airport, so Jeehan heads for the remote dune town on her own.

The decision seems rash, but Jeehan is desperate to feel at home again and prove that her “life had not been wasted.” The journey is full of obstacles. While Jeehan is Moroccan, everyone identifies her as a “khareejia,” or a foreigner. At first, the term is a reminder of her inability to feel at home anywhere, but eventually she becomes more comfortable with her own identity. But first she must undergo physical and mental healing through the love of people with fewer resources and power and their desert tribal medicine and ceremonies.

Bouziane, herself the daughter of a French mother and a Moroccan father, writes that Jeehan symbolically “came to the Sahara to be buried … to feel the heat from every grain of sand press against every inch of me scorched by the refracted fire of the sun.” The experience connects her to those who literally were buried on 9/11, and brings healing.

This is a powerful tale that takes on one of the central traumas of our time, and has something to teach us in the telling. Bouziane inspires with her story that shows the importance of taking “home” with you wherever you go, building community, and persevering against the unimaginable.

Shariatdoust is an advancement officer for leadership gifts at Babson College.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.