In mid-April, seven weeks into Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, the prime ministers of Sweden and Finland both announced they were considering joining NATO. Few, if any, stories noted that the leaders contemplating such a fraught decision—Moscow has threatened retaliation—are women. At the funeral of Madeleine Korbel Albright ’59 at the Washington National Cathedral in late April, while the war in Ukraine raged on, she was celebrated for championing democracy—and breaking one of the world’s hardest glass ceilings. But fully breaking through in the United States has proved to be harder than many expected in 1997, when Albright became this country’s first female secretary of state. Angela Merkel stepped down last December after 16 years as Germany’s chancellor, and women are prime ministers of four of the five Nordic states. The U.S. has yet even to have a female secretary of defense.

For those of us who followed her career and followed her—I covered State for the Wall Street Journal—Albright didn’t make her ascent look easy. Washington wouldn’t let that happen. And she was too candid, too self-revelatory, and too determined to teach others—especially younger women—to gloss over the challenges, the slights, or her own missteps.

When she was asked—often—if she had been condescended to by leaders from male-dominated cultures, Albright said no, because wherever she arrived, it was “in a large plane with ‘United States of America’ emblazoned on the side.” She had more problems “with some of the men in my own government.”

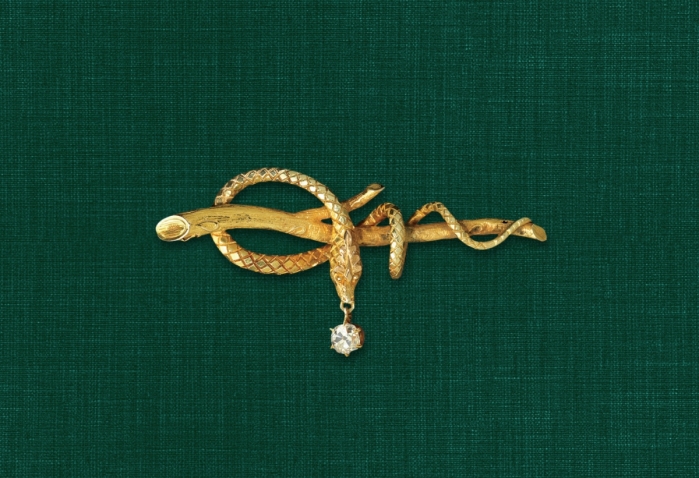

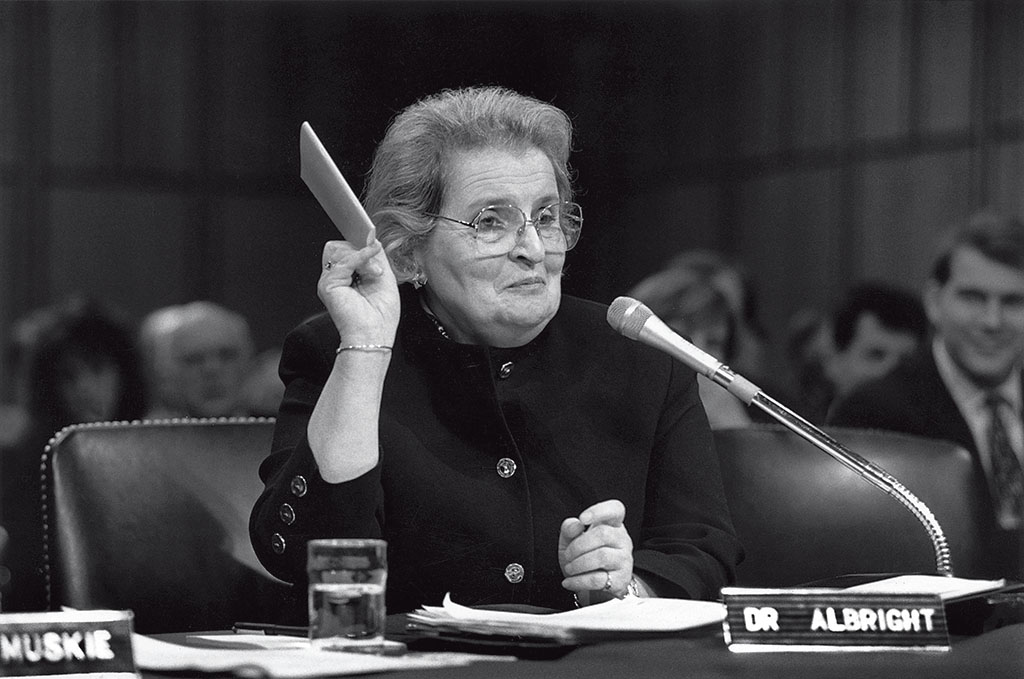

U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Madeleine Korbel Albright ’59 votes during a Security Council meeting on April 14, 1995, to allow Iraq to export a limited amount of oil to cover the cost of humanitarian supplies for its population. Albright wears her iconic serpent pin.

Timothy Clary/AFP via Getty Images

During her annual January meetings at the Madeleine Korbel Albright Institute for Global Affairs, which she and the College founded in 2009 (see “The Mentor,”), she would invite fellows to ask her any question. Saraphin Dhanani ’16, a former fellow and former member of the institute’s ambassadors council, remembers one student asking if Albright ever felt inarticulate. Albright “let out an emphatic yes. She shared how she’d only recently spoken at the U.N. and was met with blank stares. She said something along the lines of, ‘I thought to myself, is what I’m saying even making sense to these people?’”

I first got to know Albright by proxy in the mid-1980s. One of her best Wellesley friends, the late Emily Cohen MacFarquhar ’59, was my foreign editor at US News & World Report. A wonderful mixture of tough-mindedness acquired from years at the Economist and sisterly support—when I was in dangerous places, she ended conversations with “Be careful, I love you”—Emily was extraordinarily proud of Madeleine and kept me apprised of her rising Washington career. Albright only became newsworthy when president-elect Bill Clinton chose her as his ambassador to the United Nations and also named her to his cabinet and the inner circle that deliberated on national security options.

None of Clinton’s choices elicited great enthusiasm from the D.C. elite, but Albright came in for particular dismissal: She was seen as a Georgetown hostess turned political staffer, not as a strategic thinker. At a New Year’s Eve party, a conservative-leaning columnist from the New Republic sniffed to me that Albright wasn’t tough enough since she had opposed the 1990 Gulf War. Never mind that most key Democrats had also opposed the war.

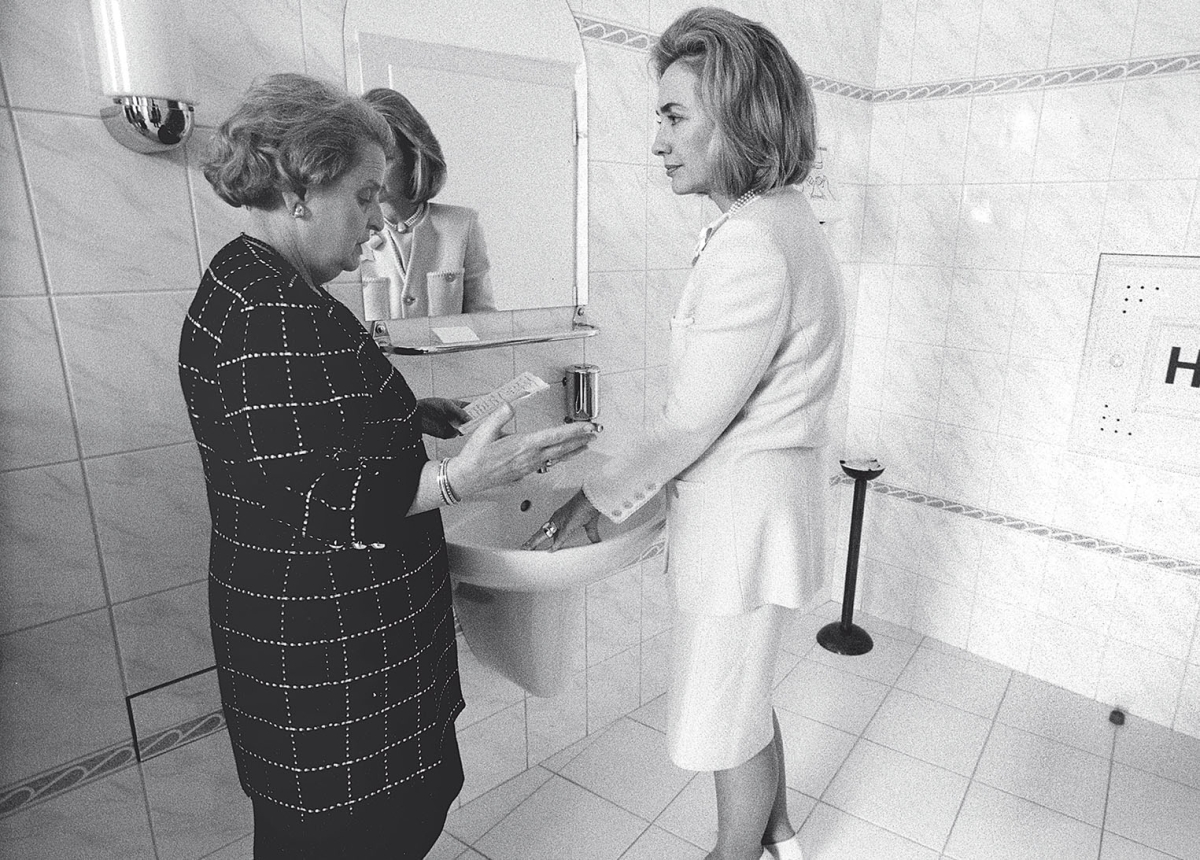

Albright briefs First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton in a ladies room during a trip to Prague in 1997.

Barbara Kinney/William J. Clinton Library

Four years later, when Albright was on Clinton’s short list for secretary of state, nobody questioned her toughness. She pushed Clinton to launch airstrikes to halt the Serbian rampage in Bosnia. At the U.N., she horrified old school diplomats and delighted everyone else when she denounced the Castro government for shooting down and killing two Cuban exiles flying unarmed Cessnas. “Frankly, this is not cojones. This is cowardice,” she told the U.N. Security Council. Miami Cubans put her quote on bumper stickers, and Bill Clinton described it as “probably the most effective one-liner in the whole administration’s foreign policy.” He recounted the story during Albright’s funeral—probably the first time “cojones” was uttered from the cathedral’s pulpit.

Gender stereotypes still stalked her. An otherwise wonderful 1996 profile in the New York Times, “Madeleine Albright’s Audition,” begins with a cringeworthy description of her visit to Prague with then-First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton ’69: “Two middle-aged American women in smart pants suits” strolling the city streets talking “about their children, the professors they had at Wellesley College, walking, eating, and vitamins.” It ends by handicapping Albright’s chances for the secretary of state job: If Attorney General Janet Reno “should leave, and if Clinton decides he needs a woman in a serious, front-line Cabinet post, Albright would have a clear shot.” Reno stayed, and Albright got the job.

As for what it took to become secretary of state, Albright’s typical answer was that it was hard, even for a woman with a great education and, after she married into wealth, huge privilege and good child care. She was self-deprecating about her own qualities: “I was the world’s perfect staffer.” “I did the best with what I was given.” “I’m not that smart. I work very hard.” Albright later wrote that she “was truly furious” with herself for that last comment, but also recalled hearing Sandra Day O’Connor expressing doubts about her own qualifications to become the first woman on the Supreme Court.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.