After Roe v. Wade was overturned in 2022, “I basically just didn’t sleep,” says Nancy Stearns ’61. She vividly remembers what she has called “the bad old days” before Roe, when she was on the front lines of the fight to make abortion legal.

In 1969, Stearns was part of an all-women team representing some 350 women in a class-action suit challenging New York state’s restrictive abortion laws. Abramowicz v. Lefkowitz focused on women’s experiences with illegal abortion and unwanted pregnancy to argue that banning abortion except to save the mother’s life violated women’s constitutional rights. (Lefkowitz was the New York attorney general; Abramowicz was the surname of the first woman on the list of 350 willing to tell her story to the court.)

Previously, most challenges had been responses to criminal prosecutions of doctors who performed abortions. But Abramowicz v. Lefkowitz didn’t involve people defending themselves against prosecution; rather, for the first time, it raised challenges brought by the people directly affected—women who had been denied abortions by the existing law.

The case was rendered moot when the New York legislature changed the state law. But Stearns continued fighting abortion laws in New Jersey, Connecticut, and Rhode Island; the Connecticut and Rhode Island cases ended up being cited in Roe v. Wade. Meanwhile, in 1971, Stearns represented Shirley Wheeler on appeal in a high-profile case that received national attention after the state of Florida prosecuted Wheeler for obtaining an illegal abortion.

Stearns had set out to be a political scientist. In 1960, she went to Washington, D.C., as part of the Wellesley-Vassar Internship Program, where she worked for the Democratic National Committee in the period leading up to the convention that nominated John F. Kennedy for president. Those were heady days in politics. After graduate school at Berkeley, she and a friend traveled to the South to briefly volunteer for SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, supporting the Civil Rights movement. Stearns ended up staying a year, turning away from an academic career, and learning lessons about political action that would shape her life.

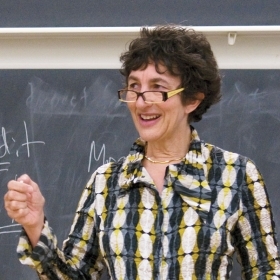

On the steps of the Thurgood Marshall U.S. Courthouse in New York City, Nancy Stearns sports a tote depicting Ruth Bader Ginsburg. This photo was taken on the late Supreme Court Justice’s birthday.

After law school at NYU, her first job involved challenges to the constitutionality of House Un-American Activities Committee subpoenas. She went to work for the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York City and was soon involved with Health PAC, the Health Policy Advisory Committee. “That’s really, I think, what led me to being involved in the women’s movement,” Stearns told the New York Times in July 2022. “Women needed a movement just like the Civil Rights movement.”

This spring, we spoke with Stearns about the roots of her activism and how she sees the future of reproductive rights. We caught up with her on one of her two weekdays off; now in her 80s, she works as principal court attorney in the Law Department of the New York State Supreme Court.

(This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

Catherine Grace: How did you get involved with SNCC in the 1960s and with activism overall?

Nancy Stearns: My family were liberal Democrats. We basically talked politics over the dinner table every night. We got a TV set when I was in junior high so my mother could watch the Army-McCarthy hearings. After Wellesley, I went to graduate school at Berkeley and was getting a master’s in political science. The then-chairman of SNCC came to do fundraising. I heard him talk and was very moved. I had gotten friendly with this guy who was very political, and he decided he would drive to the South for the summer to learn more about what was going on, volunteer to help, and just be down there. And I said I would go with him. Basically, I got hooked and stayed for a year, through the Mississippi Freedom Summer. I kind of knew by then I wasn’t an academic, that I really wasn’t Ph.D. material. I just wanted to keep working, because of the people, because of the cause. Joining a movement is an extraordinary feeling of being part of something larger than yourself that you really believe in.

“Joining a movement is an extraordinary feeling of being part of something larger than yourself that you really believe in.”

—Nancy Stearns ’61

Grace: How did that decision change your trajectory?

Stearns: Being in the South made me realize that if I really wanted to make any kind of serious contribution, I needed a skill. So, I applied to law school. My first full-time job out of law school was working on two cases challenging the constitutionality of subpoenas issued by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Grace: How did you first get involved in reproductive rights work?

Stearns: I got hired by the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) as a staff attorney. During the summer of ’69, I met a woman who worked for Health PAC, a nonprofit that worked on health care issues. And somehow or other, we started talking about abortion. And I started talking about the fact that I thought the restrictive abortion laws were unconstitutional. And she said, “Well, do you want to come to [a meeting] to meet other Health PAC women and talk to them?” I ended up in their discussions, and they liked the idea of challenging the New York law. We decided to have meetings around the city for women to be able to talk about their experiences with the health care system in general. If anybody wanted to talk about abortion, they could—if they’d had one or hadn’t been able to get one or whatever. Ultimately, we asked them if they wanted to be part of a challenge to New York’s abortion law. And they wanted to talk. Because I worked for the CCR, and I knew [lawyers] who had done litigation in the South, I had learned their techniques: Basically, having the people who are being harmed by the laws themselves becoming plaintiffs, to challenge those laws directly, telling their own stories—you know, those are real, palpable, visceral stories. Until then, we didn’t have women going into court and saying, “Hey, I’m the one impacted by these laws. And I want you to hear the story from me and understand my perspective.” That was what was different, and that was what I learned from watching what [the lawyers] did in the Civil Rights movement.

Grace: What was that first day in court for the case of Abramowicz v. Lefkowitz like?

Stearns: I remember bits and snatches, but it’s now more than 50 years ago. What I do remember is we did have a courtroom full of women. And some of them had babies, and some of them carried coat hangers as symbols of the tools that historically some desperate women were compelled to resort to to end an unwanted pregnancy.

Grace: You got involved in supporting Shirley Wheeler, who was prosecuted for manslaughter for obtaining an illegal abortion. What was the significance of that case?

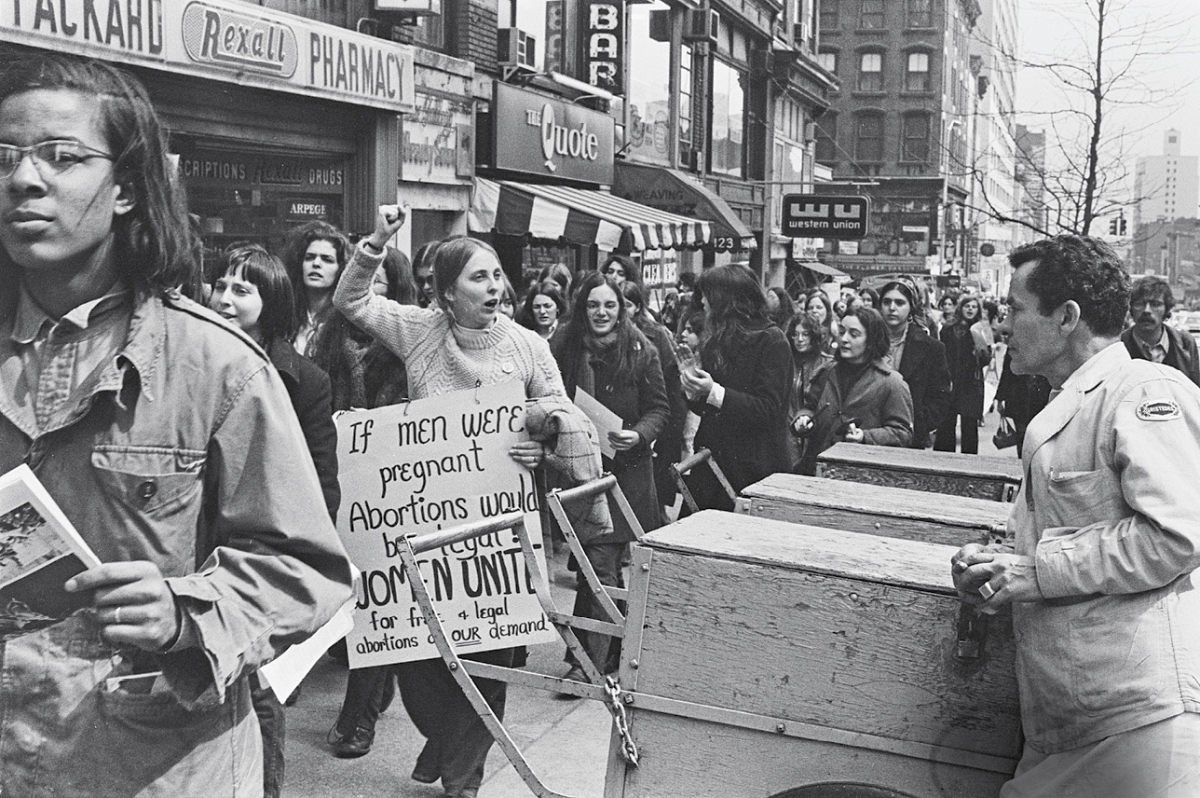

Protestors in New York City in 1970

Photo by Graphic House/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

On March 28, 1970, people protesting restrictive abortion laws marched through New York City.

Photo by Graphic House/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 1972, members of the Mountain State Abortion Coalition form a picket line at the State Capitol in Denver.

Photo by David Cupp/The Denver Post via Getty Images

Stearns: Shirley was one of the first women who was prosecuted for having had an abortion. … The prosecutor told her that she could avoid prosecution if she would give him the name of the doctor that performed her abortion, but Shirley was grateful that he had helped her, and she was willing to face prosecution rather than give his name to the prosecutor. When she was convicted, the judge told her that he would sentence her to jail if she did not marry the man she had been living with or leave the state and go home to live with her family. She was not a child, even though the judge treated her like one. She was a young woman in her 20s. Fortunately, after she was convicted, the Florida Supreme Court struck down Florida’s abortion statute in another case, and she did not have to make that decision. Before Shirley’s trial, the women’s movement learned about her story and gave her tremendous support that helped her get through her ordeal. It is important now for people to know about Shirley’s case because I fear we will be seeing more Shirley Wheelers as anti-abortion states pass more and more draconian laws—and many have made it clear that they have every intention of going after the women who seek abortions, not just the doctors.

Grace: How did this Supreme Court get to the place of overturning Roe?

Stearns: For a number of years, the Republican Party has systematically appointed judges who were anti-abortion in order to overturn Roe v. Wade. The Republicans have had [Roe] in their sights since 1973, and the Democrats have been blind. Nobody really was willing to see down the road. I wrote an article years ago saying, you know, the anti-abortion forces are fighting to undermine and even destroy Roe, but supporters of the right to abortion thought we had won. So they went home, and stayed home, not believing our rights were still under threat. Many people have asked me if Roe v. Wade had been decided on a different theory—maybe equal protection—things would be different now and Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization wouldn’t have happened. But the problem is not the theory on which Roe was decided. The problem is the six people who are now the majority. When I read the extraordinary dissent from the majority decision in Dobbs I was astounded because I thought, wow, these are Supreme Court judges saying the reason the majority reversed Roe v. Wade was not because of legal theory, it was because those justices detested Roe from the start. That is a really shocking thing for a Supreme Court justice to say.

Nancy Stearns works the phone at home.

Grace: Do you feel any optimism about the future of abortion rights?

Stearns: Yes, I think we can win back our rights, because we must. But young people must lead the struggle, because it is they who have the most to lose. But they can’t, and shouldn’t, try to do it alone. They should work with people and organizations who are now in the struggle, and many who have been for years. And they should reach out to all sorts of people who are likely to suffer the most from what has happened—poor women, women of color, the LGBTQ+ community—because only then will they truly understand the full scope of the problem, and together they will be stronger and more successful.

Grace: What will that take?

Stearns: They must use all available tools—demonstrations, legal actions, the voting booth, etc., but they must be strategic. For example, trying to get abortion rights legislation passed in states where the legislature has been gerrymandered is likely to be pretty useless and just drain them of energy. But figuring out how to get a statewide referendum passed in even a gerrymandered state, as they did in Kansas, could be well worth the fight, because as we know, the majority of Americans support the right to abortion, even if cynical legislators vote to deny us that right, and it’s politically important to work to bring those [people] out to vote for our rights.

Everyone who is fighting to protect the right to abortion should recognize that this is basically a fight about religion. The laws barring abortion are based on the firmly held religious belief that a fetus—even a fertilized egg—is a human being from the moment of conception. Religious beliefs are also being used to justify denying other fundamental rights as well, rights like marriage equality and gender-affirming care. But one of the most basic notions on which our country was founded was the separation of church and state. The First Amendment was enacted to prohibit the establishment of religion to guarantee that the religious beliefs of some will not be enacted into law and imposed on others.

But mostly, it is crucial for young people to believe that they can and must fight, and they can and must win—though it will be a long haul. The student movement played a crucial role in the development of the Southern Civil Rights movement of the ’60s. Students and other young people can and must play a similar role now, and they should understand that being part of such a movement will give them energy, strength, and a sense of purpose that will mean more to them throughout their lifetimes than they can possibly know.

Grace: To end on a lighter note, I understand you’ve been a cabaret singer.

Stearns: Yes. If you put my name in Google, you’ll get to my website. I’ve always loved to sing. In college and grad school I was into folk music. Later, [a friend] gave me a voice lesson for a birthday present. And then I was in the Broadway at 92Y Chorus for a few years. When I [began working at the New York State Supreme Court], one of my first friends at the court told me that shortly after we met, he had a dream about me that I was singing in a cabaret with a piano and a bass. He is a phenomenal singer and had been taking a cabaret class. I went to his class show, and then I went to his solo show. I started taking the cabaret class, and one thing led to another. I started doing solo shows. One of my first solo shows was called “The Words of Women,” with songs by women lyricists. The last show I did just before the pandemic was called “Women’s Lives.” And I actually did talk about doing abortion litigation. I love music, and I was able to do shows to talk about issues I cared about. I doubt that I’ll do another show, but I was so lucky to be able to make the music I did and to become part of the New York cabaret community.

Catherine O’Neill Grace is senior associate editor of this magazine. Like Nancy Stearns ’61, she grew up talking politics at the dinner table: Her father worked for the U.S. State Department in the 1960s.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.