Around 1 p.m. a couple days before Thanksgiving in 2014, I was taking the subway into Manhattan so I could catch a bus to visit a friend in Boston. Since I’m a writer and sit most days, I stand when I ride the subway and attempt to “surf,” instead of leaning against the doors or holding onto a pole.

On this particular train, my suitcase was between my feet, and I was standing a few inches in front of a door. An M.T.A. employee and the train’s conductor were working on a switch on the wall near me. As we sped between two stations, one of them pressed something that made the door behind me suddenly open. The sound from the dark tunnel was deafening, and over my shoulder, I could see the rusted poles that divide the tracks blur together. The employee let out a loud scream and grabbed my arm as the door slowly closed. If I’d been leaning against it, I would have fallen out.

When the train came to a stop at the next station, I shook her hand off my arm. Black dots swarmed in my eyes, and I moved so I could hold on to a pole. Everyone in the train was staring at me, and my face burned. The conductor shut down our train a few stops later. Instead of waiting for the next one, I ran with my suitcase up the stairs and out of the station.

This experience would have been deeply unsettling for anyone, but the fragility of life is not a concept to which I needed more exposure. In the previous 11 months, I’d lost two uncles and my grandmother. Even before my first uncle died, I’d been thinking about death on a daily basis, the fear of oblivion often punching me in the chest as I was about to fall asleep and sending me into a near panic attack.

I hadn’t always felt that sense of fear. The possibility of my own death hadn’t occurred to me until I was about 22. My ignorance had to do with the fact that I’d spent most of my time at Wellesley being strongly convinced by the Christian narrative, which included the mysterious but reassuring notion of an afterlife. It wasn’t just that, though—it was also straight-up arrogance. The same arrogance that makes people drive too fast or have unprotected sex. I believed I would wake up each day the way I believed the sun would rise.

That arrogance is gone. My latest reminder of our fragility came only a few days after I almost fell out of the subway. I was writing at a coffee shop near my apartment, when I missed a call from one of my oldest friends. I texted her and asked if she’d meant to call me. She texted back: “Yeah, my mom died.”

Her mother, Louise, was like my second mother. She was one of the first female physicians in our hometown in Montana, and a mainstay of our community. Her death was unexpected and devastating. I flew home and spent the week with my friend sorting through her mother’s belongings and planning the memorial service.

Going through Louise’s things was both a salve and a trigger for our tears. Her belongings reminded us of her curiosity. They reminded us that she’d made thousands of tiny choices to live loudly, to feast her mind on everything she could. The banjo she was briefly convinced she could master. Camera equipment she’d acquired for a trip to see polar bears in Antarctica. A room teeming with beads she’d used to make jewelry for friends, coworkers, and patients. Hundreds of good books, many filled with thoughtful notes. Each item was an artifact of a captivating life—one that, while cut short, was lived intensely and with intention.

After Louise died, my fear of death strangely began to give way, making room for conviction about how I will spend my moments. What a miracle it is to be here at all, to experience the beauty, pain, and delight that populate my ordinary world. What a gift to feel called to make art out of those things.

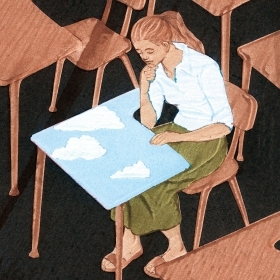

I got into a cab after the incident on the subway, and my phone buzzed with work emails and texts from a friend with pictures of a dress she wanted to buy. One of my favorite songs played through my headphones. Despite the lingering terror that continued to make my heart thud against the torn leather seats of the cab, gratitude suffused my body. Air from my open window blew against my face, and the sky was an even blue.

Thank you, I thought. Thank you.

Reece lives in Brooklyn and recently left her job with Sarah Lawrence magazine to start her own business as a writer, editor, and photographer.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.