Writing memoir is a messy business, and no one knows this better than Helen Fremont ’78.

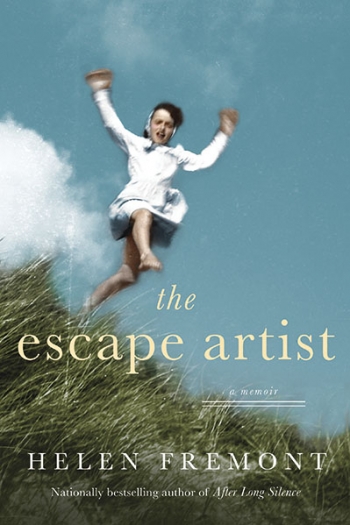

Fremont’s book The Escape Artist serves as a sequel of sorts to her memoir After Long Silence, published in 1999. After Long Silence grapples with the secret Fremont’s parents kept from her and her sister for most of their lives: that they were Jewish Holocaust survivors. Though Fremont and her sister knew their parents had survived World War II, fleeing their Polish hometown, the daughters were raised Catholic. This false religious identity was one their parents assumed to flee Europe, and, to protect those who helped them, it was an identity they kept up until Fremont and her sister were in their 30s. Upon discovery of the truth, Fremont wrote After Long Silence, revealing the secret her parents had kept for over 50 years. “I’d lived my whole life in my parents’ fiction, governed by lies and secrets and half-truths,” writes Fremont in The Escape Artist, about After Long Silence. “I needed to write something that was my own truth.” Truth exposed; case closed.

But even if a memoir ends with a tidy resolution, rarely does life tie up so nicely. The Escape Artist picks up 20 years later, and it addresses the fallout after the publication of After Long Silence. Fremont’s mother and sister stopped speaking to her for three years, and Fremont communicated with her father only through letters until his death. Even after her father died, when Fremont reconciled with her mother and sister, things were not the same: Her parents had rewritten their wills so Fremont was “predeceased,” leaving all their assets to her sister. In The Escape Artist, Fremont grapples with these painful consequences (“I could either continue to live a lie, and remain in my family; or I could lose my sister and my family, but speak my own truth”). But she also digs deep into her family’s history to try to understand the complications of a life built on secrecy. “It’s instinctive to search for meaning, to arrange and rearrange the pieces of the puzzle in such a way that they fit, that there is a satisfying snap of recognition, a sense of truth, of something resonating deeply,” writes Fremont.

For any reader, The Escape Artist is engrossing, complex, and difficult to believe, proving truth is stranger than fiction. But it is a must-read for those writing memoirs of their own—not to warn of the bad things that can result from publication, but because Fremont puts herself under a sharp lens while also showing great empathy for those who caused her pain. The best memoirs always get at the complexities and contradictions of human nature—no one is purely good or bad—and Fremont examines and tries to understand why she, her sister, and her parents did what they did. Fremont’s prose is raw yet generous in a way all writers of memoir should aspire to, and in a way all humans should approach treating and understanding one another.

Bartels is the author of Good Grief: On Loving Pets Here and Hereafter, a book about the ways we mourn and remember our pets, forthcoming from Houghton Miffliin in winter 2022. To subscribe to her monthly newsletter, go to ebbartels.com.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.