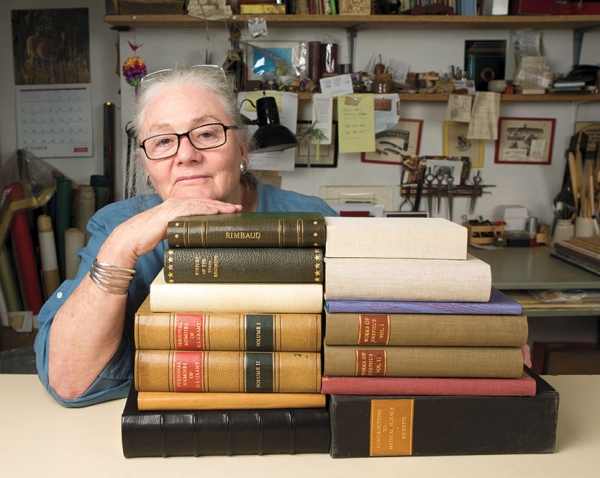

Photo by Anna Prior

When Elisabeth “Betsy” Palmer Eldridge ’59 was at Wellesley, she decided to major in philosophy and mathematics, but not out of any particular passion for the subjects. “I had some sort of harebrained idea that I should take at Wellesley all the things that I would never learn otherwise,” she says. Her passion found her anyway, when she walked into the Book Arts Lab in Clapp Library.

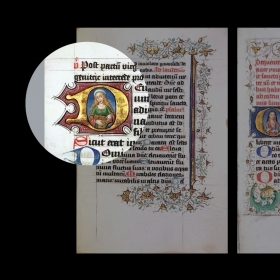

At the time, Hannah French, then director of Special Collections, offered a noncredit weekly course in the evenings that involved both examining books and manuscripts from Special Collections and creating pieces using the lab’s Washington press. “Wellesley has a remarkably good selection of early printing and so on. And so Hannah would walk us through historical printing, historical binding, all of that, with these wonderful examples. I had never seen things that lovely before,” Betsy says.

When Betsy went home to Chicago over the summer, Hannah suggested that she connect with Carolyn Price Horton ’31, a bookbinder and conservator who lived in the city at the time. Coincidentally, Betsy’s father was having some books bound by Horton, including letters and memorabilia from his 60th birthday. “I went over and spent two days with her. One day was just taking apart a book, which I thought was pretty fascinating, and then the second day was putting it back together,” she says.

Carolyn also introduced Betsy to Harold Tribolet, head of small hand bindery within RR Donnelley, a large printing company. Carolyn and Harold told Betsy that if she wanting to continue studying book binding, there really was no place in the United States to do it—she’d have to go to Europe. Luckily, Betsy’s parents were supportive, and bought her a round-trip flight to Europe as a graduation gift. “I went over to basically seek my fortune,” Betsy says. At that point, she thought bookbinding was just an interesting hobby.

Over the course of a year, Betsy traveled to Paris and Vienna, eventually landing at a small bindery outside Hamburg, Germany, where she became an apprentice. “I paid him nothing, and he paid me nothing, and I just worked for what I learned,” she says. She learned an enormous amount about the construction of books, and enjoyed the company—the staff at the bindery sang a cappella all day. She returned home to Chicago and worked as a receptionist at a hospital before returning to Europe, this time to study bookbinding at l’École Estienne in Paris. When she came back to the States, she decided to officially make bookbinding her vocation, and began working with Carolyn, who had since moved to New York City to found her own bindery.

In addition to bookbinding, Carolyn was an accomplished conservator, at a time when such skills were extremely rare. “The conservation field didn’t exist at that point,” Betsy says, and she thinks Carolyn may have been the first conservator in the United States. Through Carolyn, Betsy began to appreciate the science of paper and books, as well as their art and history.

By 1973, Betsy moved with her husband to Toronto for his work, and she opened her own independent book and paper private practice. After the Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild was founded in 1983, she began to design and teach its courses and workshops. Among the most memorable projects she’s worked on is a prayer book from 1265. “Poor thing. … Most of the initials, which had been decorated initials originally, had been cut out,” she says. Another unique project was restoring the medical record of Leonard Thompson, who in 1922 became the first person to receive insulin for the treatment of Type 1 diabetes. “What an interesting problem. It had six different types of paper. There were lab paper tests and all these different types of records. And, you can imagine, a dozen or more different pens, since all the doctors wrote with different pens,” she says.

Lately, Betsy has focused on teaching. “I just think it’s so important to pass it on. And it’s also, it’s rather thrilling to teach,” she says. Plus, she says, at 81 years old, “I just don’t know how to quit.”

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.